For many, prairie brings to mind the sweeping grasslands of the Great Plains. Few are aware that the Palouse—traditionally thought of as a sea of wheat—was once swathed in its own prairie.

Palouse prairie is the most endangered ecosystem in the continental United States. Severely fragmented by agriculture and settlement, less than 1 percent remains.

Chris Duke (’21 PhD Biol.) cofounded the Phoenix Conservancy—dedicated to restoring endangered landscapes—in 2020 after he realized the threat to ecosystems such as Palouse prairie.

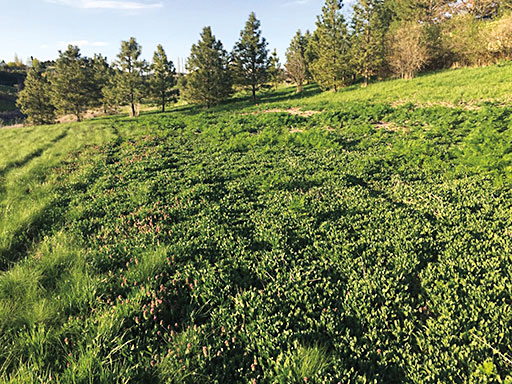

“What makes true Palouse prairie interesting and unique is it’s one of the very few forb-dominant prairies,” Duke says.

While the Great Plains are largely grass, Palouse prairie is much more diverse; in some pockets, grasses are almost absent, with dozens of herbaceous flowering plants—forbs—blooming simultaneously.

The Palouse prairie differs because “the Missoula floods largely missed our region, which is why we have the soils that allow these diverse communities to really thrive,” Duke says.

Some areas have more than 200 feet of soil. Fires were rare, allowing the ecosystem thousands of years to develop complex plant and animal communities with minimal disturbance. The three foundation plants became bluebunch wheatgrass, snowberry, and Idaho fescue. Instead of prairie dogs, Palouse prairie hosts striped Columbian ground squirrels, prey for short-eared owls, ferruginous hawks, coyotes, and American badgers. The prairie provided nourishment and shelter for wildlife, from pronghorn to sharp-tailed grouse, since the last Ice Age.

Until it was plowed.

Only a century ago, the prairie experienced widespread conversion to agriculture and was nearly lost. Now, a handful of organizations are working to save it.

Together, the Phoenix Conservancy, Palouse Conservation District, Palouse-Clearwater Environmental Institute (PCEI), Nature Conservancy, Palouse Land Trust, and Palouse Prairie Foundation (PPF) form a network of conservationists and citizen scientists. Tom Besser, professor emeritus of WSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine, is a PPF board member who first noticed prairie during his research on bighorn sheep pneumonia.

“For the first time, instead of going to farms and barns, I was going down to Hells Canyon and seeing amazing places with incredible native vegetation,” Besser says.

Pristine prairie patches exist at Whelan Cemetery near Pullman, Steptoe and Kamiak Buttes, and the Dave Skinner Ecological Preserve, named for a founding member of the PPF.

“If you go there in June, you just won’t believe how beautiful it is,” Besser says.

After heavy rain caused topsoil to cascade into his yard in 2015, Besser decided to combat the erosion with prairie reconstruction. With the help of a neighboring farmer, Besser sowed native seeds on a 3.5-acre plot. Over the past five growing seasons, he’s watched plants root into the soil and stretch leaves toward the sun. Swallows and butterflies, once just passersby, are now residents. Besser also noted that, though he didn’t plant them, native species like scarlet gilia, a twiggy forb with tubelike crimson blooms, have popped up. Their presence signals healthy pollinator activity.

Tim Pavish (’80 Comm.), who retired from his position as executive director of the WSU Alumni Association last year, moved to Pullman two decades ago. When looking for a home, thanks to PCEI and Pavish’s upbringing, he was inspired to restore habitat on the property.

“I was raised down in Walla Walla and my parents had a small farm, so I was exposed to natural places my whole life,” Pavish says.

Since starting the project, Pavish noticed a large increase in visits from deer, coyotes, and his personal favorite: great horned owls.

“The impact that you can have on habitat is significant,” says Pavish. “You don’t have to have 5,000 acres to do it. You can do it in your backyard.”

All these prairie protectors emphasize the same thing: you can do this. No matter the square footage, planting native species supports pollinators and connects isolated prairie pockets, reattracting species like ground squirrels and owls.

“That’s the most promising thing about the future of Palouse prairie: the building blocks are still here,” Duke says. “But they won’t be forever.”

Here are plants of the Palouse prairie that were valued by Native Americans include bluebunch wheatgrass, Idaho fescue, fernleaf desert parsley, arrowleaf balsamroot, spreading dogbane, common chokecherry, Nootka rose, creeping Oregon grape, large-fruit desert parsley, black hawthorn, nettleleaf horse mint, wild strawberry, tapertip onion, and common camas (From The Palouse Prairie, A Vanishing Indigenous Peoples Garden. Photos Wikimedia Commons)

The Palouse Prairie Field Guide helps plant enthusiasts identify native plants found in the Inland Northwest prairie regions of Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and Montana. David Skinner ’70 was a coauthor.

Web exclusives

More information on all the Palouse prairie preserves and reserves listed in the story