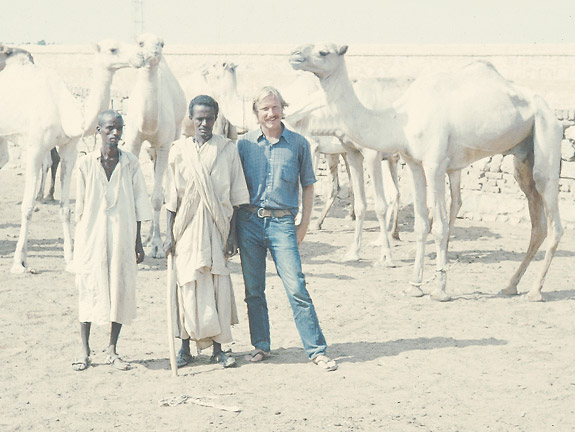

Fresh out of college in 1971, with a little money saved up, Barry Hewlett bought a one-way ticket to Europe. He trekked around Europe for a while, but eventually started to get bored. He noticed many of his fellow youthful travelers were heading for India. So he headed south, for Africa.

He found a cargo boat that was going to Alexandria, Egypt, and booked passage. And kept going, up the Nile to Khartoum in Sudan. Along the way, he says, other travelers told him, you’ve got to see the pygmy people. So he made his way to Uganda to visit pygmies.

He didn’t stay long, he says. It was his visit two years later that would determine his career and relationship with a hunter-gatherer people who eventually would offer him much insight into human cultural evolution.

Hewlett started thinking about graduate work. He saved a little money and two years later flew to Paris, then to Marseille, and then took a boat to Algiers. He had in mind a survey of forest people, of pygmies, west to east across the Congo. He had no funding. At 23 he had begun an intriguing career, with his own money, the cheapest way possible.

Having reached the Central African Republic, he joined two other travelers who had decided they wanted to go live with the pygmies for the rest of their lives. They found a villager to take them into the forest. But ten miles down the road, the villager stopped, having decided he didn’t really want to go. The forest was a scary place.

Well, just tell us how to get there, they said. Follow the trail, stay to the right, he told them as he turned around to head back to the safety of the village.

After seven hours of walking and staying to the right, Hewlett’s companions, who were carrying huge backpacks, were exhausted. Maybe they didn’t want to spend the rest of their lives with pygmies after all. We’re going back, they said. Hewlett never saw them again.

He walked a few more hours by himself, then set up camp deep in the jungle. The next day, he had walked another four hours or so when he encountered another person, a villager, not a pygmy. Keep walking, he was told. Just follow the trail and stay to the right.

Finally, toward the end of the day, Hewlett found a pygmy camp. But they took one look at him and ran away. They’d never seen a mundju before. He must be a spirit.

Eventually, however, some men came back, their curiosity about this strange white man overcoming their fear.

“That,” says Hewlett, now a professor of anthropology at WSU Vancouver, “was my first time with the Aka.”

The Aka pygmies, a hunter and gatherer people, occupy the southwestern regions of the Central African Republic and Congo, across an area of approximately 100,000 kilometers. They share the area and interact with over twenty agricultural groups.

After the 1930s, there were several attempts to settle them, but to no avail. Currently, there are approximately 20,000 Aka.

The Aka are known as skilled elephant hunters, but utilize nearly 30 species of game, twenty insect species, eight types of honey, and many plant species. Hunting increases during the dry season.

The Aka generally reside in camps of 20 to 35 individuals, consisting of one to 15 families.

Since his first couple of visits, Hewlett has returned to Africa nearly every year since and now has a home there, having dedicated his career to understanding a group that represents better than 95 percent of human history.

In the opening chapter to the recent Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods, Hewlett writes, “Global capitalism has been around for about two hundred years, class stratification (chiefdoms and states) about five thousand years, simple farming and pastoralism about ten thousand years, and hunting-gathering hundreds of thousands of years… .”

That enormous portion of human history undoubtedly holds many answers as to why we are as we are—and to the reasons we have survived as a species. But because traditional hunter-gatherers are steadily being subsumed by encroaching development, the chance to study such an obviously essential part of our being is quickly disappearing.

What drew Hewlett, and what has commanded his fascination since, is an urgent desire to understand “an incredible way of life.”

Many people think of hunter-gatherers as belonging to the exotic realm of National Geographic, he says. Exotic, but not offering much in terms of applicability.

Rather, insists Hewlett, there is a long list of things we can learn from the people who live as our ancestors did, who offer a glimpse of the eons of human evolution and socialization.

Among those lessons is the Aka’s indulgent child-rearing.

Lesson: Quantity of time matters. Try to be around your children, even if you are not actively engaged with them.

Not only do we know little of the biological and cultural evolution that made us what we are, anthropologists have generally ignored children—even though children represent more than 40 percent of most populations anthropologists study.

The average age of the Aka, according to The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers, is 21. Fifty percent of the Aka are younger than 15. Both fertility and infant mortality rates are high.

Hewlett was struck by the relationship between father and child among the Aka. His dissertation on the subject became his first book, Intimate Fathers.

Aka infancy is completely indulgent, he writes. “Infants are held almost constantly, they have skin-to-skin contact most of the day as Aka seldom wear shirts or blouses, and they are nursed on demand and attended to immediately if they fuss or cry.” Three- to four-month old infants are held 91 percent of the time, much of that time by their fathers.

Whereas Western fathers are often the rough-and-tumble playmates of their children, Aka are more likely to hug and kiss them. Western fathers tend to play a more extrinsic role in the life of the child, says Hewlett, assuming the responsibility of introducing the child to the outside world. Mothers are more responsible for the emotional-social aspect. That model simply does not apply to the Aka, he says, where fathers are actively involved in all aspects of the child’s being. “Aka infant attachment to fathers seems to occur through regular and sensitive caregiving.”

Forager camps are typically very dense, often occupying a space the size of a large American dining and living room. When you sit down in an Aka camp, says Hewlett, you’re generally touching someone.

The Aka also sleep very close together and almost always with someone. Forager children and adolescents never sleep alone. In contrast, village farmer children over seven years old sleep alone 30 to 40 percent of the time.

The Aka are obviously and blithely unaware of the American Pediatric Association’s warning against sleeping with one’s infants. “If hunter- gatherers were rolling over and killing their kids, co-sleeping never would have evolved,” says Hewlett, smiling wryly. He notes also that the Aka consider our sleeping patterns as child neglect.

“Aka fathers provide more direct infant care than fathers in any other known society and provide substantially more direct infant care in the camp,” he writes in a chapter in Anthropology and Child Development.

One exception to such intimacy is childbirth. Hunter-gatherer fathers are seldom involved in childbirth, says Hewlett, though they will not be far away. The only father he’s encountered who helped with his wife’s childbirth was out hunting with her when she went into labor.

“Lesson: In a social-economic setting where parents have to be away from their children most of the day, co-sleeping with children may enhance parent-child communication.

Such intimacy requires help. No matter how long a father, or mother, is willing to hold, and tend to, an infant, he or she cannot do it all by themselves. After all, they depend on hunting and gathering to survive. The success of a group therefore depends on “allomaternal” (more than maternal) help. And not just from grandma.

Traditionally, write Hewlett and colleagues in a recent article in Science, anthropologists have suggested that hunter-gatherer co-residence is based almost entirely on kinship, that the bands and camps are all related.

What they now understand is that the evolution of cooperation and cultural capacity, as well as genetic viability, depended on certain factors.

First, bands are mainly composed of individuals either distantly related by kinship and/or marriage or unrelated altogether.

Second, large interaction networks may be required for culture to develop and accumulate. As an example, he cites an isolated group that lost its ability to make fire.

“Our foraging ancestors,” write Hewlett and colleagues, “evolved a novel social structure that emphasized bilateral kin associations, frequent brother-sister affiliation, important affinal [related by marriage] alliances, and co-residence with many unrelated individuals. How this social structure evolved, and how it in turn affected cooperation and cultural capacity—and the role of language in all these features—are key to understanding the emergence of human uniqueness.”

In addition, hunter-gatherers “often show extensive cooperation among members of a residential unit in ways not paralleled by any other primate. This includes band-wide food sharing; high levels of allomaternal child care; daily cooperative food acquisition, construction, and maintenance of living spaces and transportation of children and possessions; and provisioning of public goods on a daily basis.”

When a hunt is successful, a family will share nearly all of the meat with the rest of the camp.

Biological success “appears to be based on both cooperation with non-kin and exceptional reliance on cultural transmission, yet critical questions remain about why these traits emerged in humans but not other animals.”

In spite of such cooperative care and the physical immediacy and intimacy, children are not the center of attention in Aka culture. Adults will not interrupt their interaction or activity to tend to a child’s demands.

Also, Aka children develop as completely independent and autonomous. By three or four, an Aka child can cook a meal over a fire, use sharp knives and axes, and trap small game. By ten, he or she can survive on their own in the forest.

The Aka believe, says Hewlett, that telling your children what to do all the time is inconsistent with the value they place on respecting autonomy. The autonomy allowed an Aka child can be unsettling to an outsider. Hewlett reports toddlers playing with knives and machetes, ignored by their parents. Camp residents will, however, gently guide a child away from a fire or other immediate danger.

Autonomy is a core value among the Aka, says Hewlett. A curious side to this value, however, is that Aka children are not socialized to respect elders, respect and deference giving way to intergenerational equality.

Whatever the reason, it is interesting that Aka teenagers undergo no identity crisis—they know who they are and do not have issues about their future. There are no surly or rebellious Aka teens.

“Everybody knows what you’re like by the time you’re a teenager,” says Hewlett. “They don’t have to act out.”

Aka children spend their entire day with the same social group. In the United States, on the other hand, a child will change social groups throughout the day, from daycare to school to soccer.

Aka teens do have reputation building to consider, says Hewlett. They want to be seen as good workers. But that’s not trying to establish their identity.

Hewlett is currently most interested in what he calls “social learning,” or how individuals learn from others. Interestingly, for such a fundamental process, not a lot is known.

“There are more books on chimpanzee social learning” than on hunter-gatherer social learning.

A recent paper by Hewlett covered various aspects of social learning. First, are parents primarily responsible for transmission of culture, or peers? How does the combination vary amongst cultures, and what is the predominant means among hunter-gatherers?

With the Aka, Hewlett is realizing, early learning is primarily vertical, but with lots of horizontal.

“That’s why they place the kids facing out on their lap when holding them in camp.” We of the West generally hold our children facing us.

The same paper has been cited extensively, because it has always been thought that hunter-gatherers wouldn’t employ teaching. There is an academic faction, in fact, amongst social anthropologists, that denies teaching even exists in any small-scale cultures, especially hunter-gatherers.

Hewlett picks up a book from a nearby shelf, leafs through it, and shows me a couple of chapter titles: “Infants not seen as learners” and “Absence of teaching.”

We might just need a better definition, says a bemused Hewlett.

He concedes that such ideas have some inspiration in as esteemed a source as Margaret Mead, who characterized small-scale cultures as “learning cultures” because children acquired knowledge and skills easily, without teaching.

But social anthropologists take it further, using the word “osmosis,” referring to learning as automatic, without effort or failure.

“Social learning always takes place in a biology-culture interface,” Hewlett insists. “Social anthropologists tend to ignore biology, and evolutionary biologists tend to neglect the role of culture,” he writes.

Although such interpretations might be simply dismissed as academic positioning, or an overly romantic vision of primitive culture, Hewlett concedes that lack of proper models and tools can feed the perception.

“We don’t have existing methods for small-scale groups like this to evaluate teaching,” he says.

How children learn, who they are watching, and how many others they are watching are fundamental questions toward understanding social learning, he says.

“We need to talk with kids more, about who’s important to them.”

Referring to the social anthropologists, he says, “We need to address the academic ideas, but also I do think if we do things more systematically, we’ll be able to contribute to broader ideas.”

“Respect for autonomy and an egalitarian ethos promote self-discovery and an intrinsic motivation to learn,” he writes, acknowledging the ambiguity of learning, but firm in his conviction that natural pedagogy is universally human.

“We know very little about social learning in hunter-gatherer adolescence,” he reiterates. “Systematic research on hunter-gatherer social learning is urgently needed. This way of life will not be part of the human landscape for much longer.”

Lesson: Mothers are not the sole caregivers of infants and young children. Non-maternal care is part of the human pattern.

How children learn is only one of many fundamental questions toward understanding human evolution that Hewlett would like to understand. Besides helping to understand cultural evolution of humans, on a very practical level, an understanding of child-rearing that comes out of a culture as old as humanity itself can offer a continuity to our child-rearing in a culture that changes dramatically each generation. But our understanding of both the elemental and the applicable exudes urgency.

As old and continuous as their culture is, the Aka are not immune to change.

Some time ago, Aka representatives approached Hewlett and asked him to help them build a school. It was very important to them, says Hewlett. Although their traditional relationship with the farmers was good overall, some tried to exploit their labor and lack of education.

The Aka wanted to learn how to count money. They wanted to understand the monetary system. They wanted to learn how to speak French so they could represent themselves at local or regional meetings.

Finally, they wanted to improve the future of their children.

As an anthropologist, Hewlett was torn. “The school has been very problematic for me,” he says.

But, he adds, the idea was completely initiated by the Aka. In anthropology, it’s generally bottoms up in terms of development, he says. “We like to focus on what people say and what people want.”

So he helped them build a school. There have been rough times. Once, the roof blew off in a rainstorm. “At those times, I take the opportunity to ask, ‘Do you really want a school?’”

And each time, it’s yes, don’t stop.

But if a school and its required schedule mean a dramatic disruption in the pattern of their year, the Aka are also careful to choose what change will come to their culture.

“If they wanted more of [outside] culture, they would move closer to the city,” says Hewlett. “They don’t.”

Next year, Hewlett, his anthropologist wife Bonnie PhD ’04, and other colleagues, including former graduate student Courtney Meehan PhD ’05, now on the anthropology faculty at Pullman, will return to Africa, and he will continue his quest to understand these people who represent such a dominant segment of human cultural history.

“I love Africa,” he says. “Every day is a new lesson.”

Lesson: Indulgent care does not lead to dependent children. Indulgent care may lead to increased trust and self-esteem.