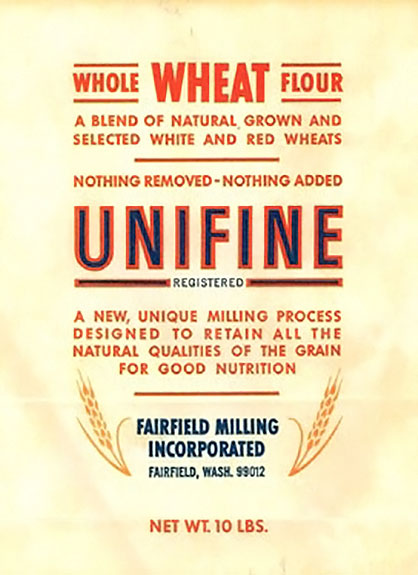

Steve Fulton grew up in the 1960s with his uncle Leonard’s flour milled with a process called Unifine. Fulton ate whole wheat bread baked by his mother Lee x’38 from the flour. His father Joseph x’39 promoted and delivered the flour all over the Northwest. But the Spokane area mill closed in 1986.

So in 2008 when Fulton started researching the family mill—built at Washington State University—he was surprised to learn that Oregon company Azure Standard was using the Unifine name for its flour.

He emailed Azure Standard’s president, David Stelzer. “David called my cell phone and said, ‘I know where your uncle’s mill is,’” says Fulton. Stelzer purchased the mill in 1999, fixed it, and had three more fabricated.

The rediscovery of the mill inspired Fulton to contact WSU researchers and learn more about the Unifine mill history and its unusual process to make fine whole grain flour.

Flour milling has come a long way from the stones used by our ancestors to grind and better digest the wild grains they found. Societies developed agriculture, and a desire to make bread and other baked goods drove the invention of grist or stone mills to further grind grains into flour.

Roller mills developed in the nineteenth century refined the flour and created an industrial-scale process. These mills use a series of rollers, first with corrugated surfaces to strip the outer hull—the bran and the germ—from wheat, and then flat rollers to reduce the endosperm into fine white flour. To make whole wheat flour, the bran and germ are processed and blended back into the white flour. Most mills still use this system for producing the flour on supermarket shelves.

The Unifine mill takes a different approach. The wheat or other grain is blown into a high-speed flywheel, which pulverizes the grain against the rough surface of the container. After one pass, the exploded material blows into a sifting system, producing whole grain flour with a very fine particle size.

The result has higher protein content, more nutrients, and a longer shelf life. Roller mills require added moisture to process wheat, which could explain the reports of less rancidity for the drier Unifine flour.

Englishman John Wright first developed the Unifine mill in England during the late 1930s, only to have it bombed during World War II. He took the idea to the United States, eventually meeting with Washington State College engineers about the technology. The mill could not be patented, but WSC controlled the registration of the name “Unifine” until 1975.

WSC researchers built a prototype and studied the milling, baking, and consumer acceptance of Unifine products from 1950 to 1958. That’s when Leonard Fulton entered the picture and secured a Washington State Grange grant to build three commercial-grade Unifine mills, which were completed in 1961. He ran one of them in Fairfield, Washington. Joseph Barron later built and ran a Unifine mill in Oakesdale.

Another mill on campus was sold as surplus in 1981 to WSU food scientist Mary Stevens ’49, who had worked on the original Unifine studies as a graduate student, and a group of WSU faculty and other investors. They started producing and selling flour as the Unifine Milling Company and the “Flourgirls” brand out of a converted chicken coop.

Eric Wegner ’79, a Pullman area farmer, joined the company as manager in 1987 and worked there until 1995 when the company went out of business.

“They needed someone who was handy and knew wheat,” he says. “I learned on the job and from scouring the old WSU technical documents.”

Wegner, who also holds WSU degrees from 2002 and 2010, now works for the USDA Western Wheat Quality Laboratory at WSU. Thinking back on Flourgirls, he says, “We were just a little bit too early for the major whole grain movement.”

Byung-Kee Baik ’94 PhD, a cereal chemist with WSU’s crop and soil sciences department, first heard of Unifine in the late 1990s after he started working at the university.

“I got a call from a lady in Seattle asking ‘Where can I find Flourgirls flour?’ I had no idea what it was,” he says.

Baik asked around the food science department where he worked and learned about the milling system from Beverly McConnell ’72, ’80 PhD, one of the original Flourgirls investors. A decade passed before he heard the name Unifine again.

In 2009, Steve Fulton contacted Baik, Wegner, and assistant research professor Pat Fuerst about Unifine after he heard about Azure Standard using the mill. The idea intrigued the three researchers and they began to examine the Unifine-produced flour’s particle size, storage potential, and quality compared to roller mill and stone mill flour.

“The anecdotal evidence was that Unifine flour goes rancid slowly. We decided to do a test of that,” says Fuerst.

They made flour from two types of wheat, hard red and soft white from single lots, on a roller mill, stone mill, and the Unifine mill at Azure Standard. The samples were tested for hexanal—a byproduct of fatty acids oxidizing that causes bad smell and taste in flour—for a year and a half.

“You could clearly see that roller mill flour turned rancid more quickly with both types of wheat, Unifine was in between, and the stone mill had the least rancidity,” says Fuerst.

Baik says the moisture content and particle size are primary factors for the difference. He points out that water is added during the roller mill process, and a stone mill’s coarse particles lowers rancidity. The Unifine flour particles are similar to the roller mill’s flour and produces similar bread, says Baik.

Fulton also gave a $10,000 grant to WSU’s engineering department to study the Unifine mill and see if they could make efficiency improvements. Engineering professor Chuck Pezeshki and his Industrial Design Clinic students made some changes and manufacturing specifications for the mill.

Azure Standard now produces about a million pounds of organic flour a year from a variety of grains and legumes for sale across the western United States. Their customers respond very positively to the ultrafine quality and nutritional benefits, particularly in the pastry flour.

Stelzer has also witnessed the storage life of the Unifine flour. “We’ve had flour sitting at room temperature for a couple of years and it seemed fine,” he says.

The shelf life, nutritional quality, and baking properties of Unifine-produced flour give Fulton hope for a bright future of the process.

“It makes no sense to mill whole wheat flour using the roller mill system that has dominated the flour industry for the last 150 years,” he says. “The time is coming when new flour mills are put on line, the compact, efficient Unifine mill will most certainly be chosen over the roller mill system.”

The market for whole wheat and other whole grain products continues to expand quickly. In 2010, whole wheat sliced bread surpassed white bread in sales for the first time.

Wegner, Fuerst, and Baik think the milling process could be ideal for smaller, local operations. They aspire to continue their research on Unifine flour, possibly with a mill on campus.

Baik and Fuerst speculate that a Unifine mill could also be built at WSU to make a whole wheat Cougar flour with extra grain from the Spillman Experimental Farm.

Web extra

Unifine Flour Cookbook from Leonard Fulton’s Fairfield Milling Co. (PDF, 2.2MB)

On the web

“Scientists collaborate to improve wheat flour” (WSU News, Oct. 27, 2011)

Unifine mill (Wikipedia)