We used to believe, says neuropsychologist Maureen Schmitter-Edgecombe, that if a person lived long enough, he or she would develop dementia.

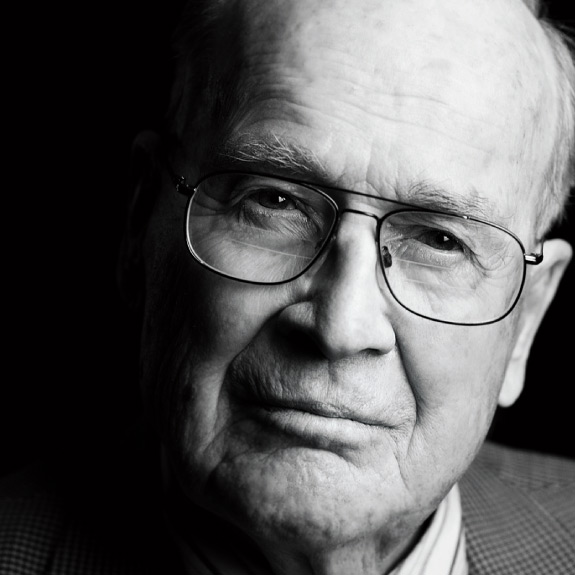

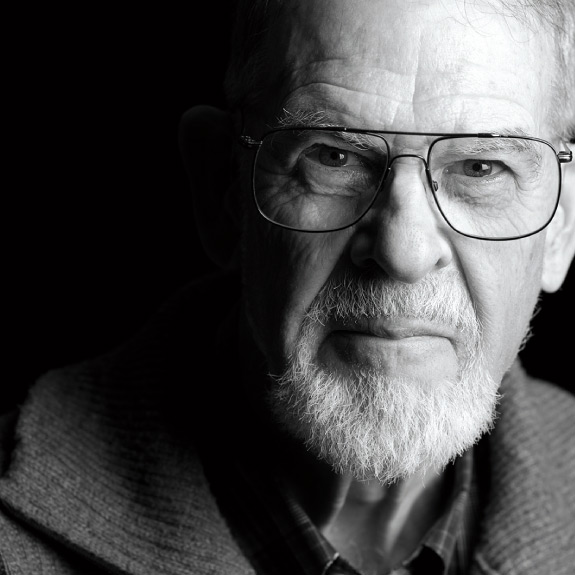

Now we know better, she says. Whether caused by Alzheimer’s or other disease, dementia is not a normal aging process. Many people, such as G. Roger Spencer and colleagues pictured here, remain completely alert and engaged well into their 80s and 90s and older.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, the chance of someone over 85 having the disease is nearly 50 percent. Other dementia-causing diseases raise that risk even higher. So what is it that enables someone to escape the dementia odds?

Besides age, there are a number of factors that indicate a higher risk of dementia: obesity, diabetes, smoking, poor nutrition. And low education level.

Conversely, the higher the level of education, the more rigorous the engagement of the mind, the lower the risk of dementia.

Indeed, the one thing these good people pictured in our photographic essay have in common, besides defying the dementia odds, is a rich life of the mind and long tenure at Washington State University.

Obviously, the benefits are not exclusive to WSU.

According to one recent study, each additional year of education translates to an 11-percent decrease in one’s risk of developing dementia.

How education and intellectual engagement protect against loss is intriguing. Does a vigorous mind protect against the onset, or does it help the individual compensate, through a quality known as “cognitive reserve”?

Recent research indicates the latter might be the case. A 2010 article in Brain by researchers from the United Kingdom and Finland reported the assessment of participants followed for up to 20 years. Participants completed extensive questionnaires and interviews regarding their education and cognitive health. Following their death, their brains were examined for pathologies. What the researchers found was that years of education did not prevent brain pathology, but rather helped individuals mitigate the effects.

The study suggests not only the importance of continuing education toward developing a cognitive reserve, but the strong effect of education early in life as a defense, indicating the value of early education as an investment in public health.

Unfortunately, statistics can be cruel. No matter the odds, someone loses. Intelligence and education are no guarantee against dementia. Many of us know a wonderful scientist here at WSU who fell on the negative side of the risk ratio and, tragically, lost his memory and self to the ravages of early Alzheimer’s.

Such an anomaly makes the research at WSU on cognitive decline and dementia particularly personal. But it’s personal also in a broader sense, touching nearly everyone. If we do not yet have a family member or friend suffering cognitive impairment, we very likely will at some point. Or we might suffer it ourselves.

But hope is not only infectious, it’s justified. If higher education gives us a cognitive reserve and helps fend off loss, researchers such as Schmitter-Edgecombe, Diane Cook, Dennis Dyck and others are striving to develop ways to compensate, while Jay Wright, Joe Harding and others have their sights set on outsmarting the affliction ultimately, by repairing the connections destroyed by dementia-causing disease.

—Tim Steury, Editor