Fantasy writer Patrick Rothfuss (’02 MA) enters the sleek atrium of the Chicago Hyatt with aplomb—passing through a lobby packed with weird characters. A human-sized rabbit taps away on a laptop, a steampunk Victorian-era archaeologist hunts for her friends, a green-haired space alien stands in line for a latte.

These are Rothfuss’s people. Or as he calls them, “Geeks of all creeds and nations.”

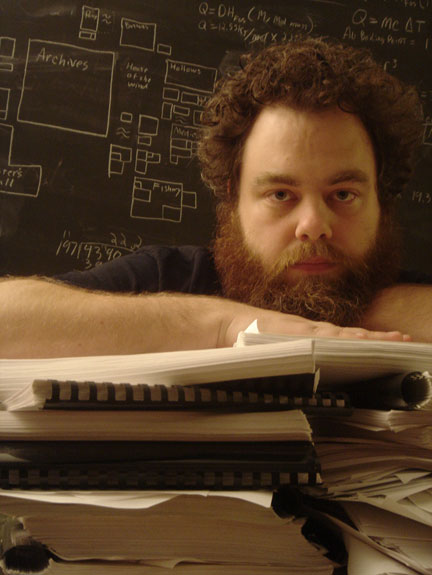

Rothfuss also looks weird. He hails from another time or place—maybe 1970s America, since Simon and Garfunkel peer out from his black t-shirt, or maybe the Middle Ages where his unruly beard would suit him in any village. Or maybe sometime or somewhere else entirely, since two locks of his hair are curling down his forehead like little horns.

He turns to give a broad smile to a cherubic little boy in a stroller behind him. The contraption is being pushed by a woman wearing a t-shirt that says “Pat’s minion.” He bends and kisses the child, who in this crowd he calls Oot—names are significant to Rothfuss. His key characters have several. Even his own son must have more than one.

“Names are important as they tell you a great deal about a person. I’ve had more names than anyone has a right to,” says Kvothe in The Wise Man’s Fear.

Rothfuss waves goodbye to his assistant and then leads me to the escalator. We’re on a quest for a spot to visit undisturbed by the writer’s fans. But the prospect of finding one seems uncertain as we work our way downstairs and through the halls filled with attendees of the September 2012 science fiction convention Chicon. People wave him down to shake his hand and ask when part three of The Kingkiller Chronicle series will be printed. One young man drops his armload of papers and pulls a small purple book (another of Rothfuss’s published works) from his backpack. “I have the princess with me,” he says handing the hardback fairy tale to Rothfuss to sign. The author beams and thanks the guy for buying the book.

Rothfuss, a New York Times best-selling author, willingly breaks his focus for his fans. He took a leave from writing at home in Wisconsin to come to Chicago at his own expense and be available, answer questions, and sign autographs. He also gets to see some of his own literary heroes. Authors like Neil Gaiman and George R. R. Martin are somewhere in the hotel along with dozens of other well-known writers, editors, and publishers from the science fiction and fantasy world. This, Rothfuss says, is the main industry event.

We finally tuck in to a quiet corner to talk about his life as a fantasy writer, his fairly newfound fame, his world in Wisconsin, and his dark days as a graduate student at Washington State University.

A story to tell

While the expected science fiction and fantasy names often surface around Rothfuss—Joss Whedon, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis—some unexpected literary influences come up just as quickly. Rothfuss, who lacked cable TV as a child, was a voracious reader. He had a steady diet of books like The Chronicles of Narnia and The Dragonriders of Pern.

There’s a kindness to this guy as he explains for perhaps the thousandth time that he may have always been in the process of writing a book. But what sealed his focus on telling the story of Kvothe, a warrior, performer, and magician, may have been, of all things, the 1897 play Cyrano de Bergerac. Rothfuss loved the poetry of the play, the marvelous character of Cyrano, and the deep tragedy of a man who died in the arms of the woman who for years he had loved from afar.

Rothfuss paints the scene of his awakening: “It was like this beautiful sunny Saturday. I had the house to myself. I’d been there in college for three years. I’m reading this play and its beautiful language.

“For the last quarter of the book, it’s just heart wrenching. I’m reading it and I’m wiping the tears out of my eyes. I finished the play and I’m like ‘Geaahh. I’ve got to move on with my life.’ I go upstairs and I walk around and I’m just crying. I go back downstairs and I’m still crying.

“After I got control of myself, I wondered how come I’ve never read a fantasy book that is this good.”

Around that time, he had picked up the autobiography of Casanova, an eighteenth century Italian nobleman who gambled, seduced women, and had many scandals and adventures. “It was amazing, the story of this man’s life. He was so full of himself. He would take these incredible risks and make these huge mistakes,” says Rothfuss. Again, he wondered why he had never found anything like it in fantasy. In some ways, Rothfuss’s books are like Casanova’s story, full of adventures and exploits, told in the first person by an imperfect hero.

Finally, when it comes to influences, Rothfuss brings up Gwendolyn Brooks, the African-American poet who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1950. Not only was he caught up with the music of her poems, but her live reading astonished him. “It was one of the first in-person readings I ever attended,” he says. “Everyone was gripped.” In between her poems, she would tell these great little stories about her life and how her poems came to be. “That’s what I remember from that,” he says.

As Rothfuss writes, he works in side stories and details of many of the things that fascinate him. His first book, The Name of the Wind,tells of a young hero’s awakening. Born a precocious child of traveling performers in a bucolic Thomas Hardy-like countryside, tragedy strikes him. He loses his family, faces supernatural beings, and finishes his youth as a street urchin in a Dickensian city. In the end he finds his way off the street and into a school of magic. The Wise Man’s Fear, book two,features the hero attending the university, a skilled but unruly student competing with his classmates and struggling with his finances. The third book, which Rothfuss is now editing and revising and about which he reveals little, is called The Doors of Stone.

Pat’s own dragons

Universities are a theme in Rothfuss’s life and his books. It seems he has always been on or near a campus since he started college at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. He took courses in medieval history, theater, anthropology, and English. “Given my casual stroll through college, I was able to accumulate a lot of experience that maybe a lot of focused students wouldn’t have had the opportunity to do,” he says.

Most of the time, he was working doggedly on his trilogy, filling thousands of pages with the stories of Kvothe and details of the Four Corners world, which Rothfuss describes as another place, right now.

But if you hang around long enough, the school starts to notice. English Department Chair Michael Williams (’75, ’85) called him into his office and told him he needed to graduate. Rothfuss thought about what he would like to do—and a life in academia seemed a good fit. After nine years as an undergraduate and seven years as a writing tutor, he was already off to a good start. So he set his sights on graduate school, and because some of the Stevens Point faculty, including Williams, had attended WSU, he aimed for Pullman.

“I had been a tutor in the writing lab for so long, I was training the tutors,” he says. That surely factored in to his application, since as a graduate student he would be teaching and helping WSU freshmen with their writing. “I do not look like any sort of sensible applicant on paper,” says Rothfuss. He was once on academic probation. He failed Math 106 several times because he didn’t like the professor. “My record was spotty. It had character.”

When he got to Pullman, he found most of his classmates were quite different. They were intense and focused; many had finished college in three years after testing out of the freshman courses. At graduate student orientation, the new students were asked who had taken English 101 as undergraduates. Only Rothfuss and one other raised their hands. That was Patrick Johnson (’98, ’99, ’02).

Rothfuss latched on to Johnson, who had a similar tendency to linger around campus. “I was sort of addicted to Pullman school life,” says Johnson, a Vancouver native who had by that time been in Pullman six years. “He saved my life,” says Rothfuss. “Without him, I never would have finished graduate school.” Johnson won’t take that credit, but admits the two Pats helped each other. “I knew the WSU system. I knew the faculty,” says Johnson. “I helped him find an instant group of friends.”

Rothfuss wasn’t hard to befriend. “Pat is one of the most charismatic persons that I have met,” says Johnson. He remembers a time on campus when the two were walking past a demonstration on the Glenn Terrell Mall. It was a rally about racism, says Johnson. The ASWSU president asked if anyone wanted to speak. Though he had only been on campus about three weeks, Rothfuss raised his hand and took the microphone. “He said, ‘I like what I’m hearing,’” and went on to praise the group for being progressive and open minded. It wasn’t much for content, says Johnson, “But he couldn’t resist the opportunity to speak to a group of people.”

The friends were good, but the rigorous schedule and the tenor of the graduate work didn’t fit Rothfuss. “I’m not in any sense suited to be a modern day academic scholar,” he says. “I probably would have been fashionable like 300 years ago or 2,000 years ago. Those are my sweet spots. The scholarship that is done these days, I really don’t have a taste for. The sort of things I wanted to research and I wanted to write about didn’t seem really sensible to a lot of the profs that I talked to.”

Johnson understood his friend’s struggle. “We had two years to teach classes and take classes… and there was more scrutiny, more judgment,” says Johnson. “It took away all his freedom. I felt exactly the same way. It ruined school a little bit for us both.”

But it helped Rothfuss further define himself and connect with the people around him. He also found some teachers he loved. Michael Hanly’s courses in Chaucer and Medieval studies were among his favorites. “He was teaching in areas I was most historically interested in. And he was a great lecturer.” He also had to fight to get into Bill Condon’s class on the assessment of writing. “He opened my eyes to how to really do a good job in a composition classroom,” he says. “And I found out that I love to teach. I really love to teach.” Rothfuss claims Condon’s was the most beneficial class he took in graduate school.

Rothfuss’s classmates were interested in being scholars and in writing poetry or, what he pronounces with a highbrow accent, literary fiction. His own efforts in fantasy were sometimes viewed with disdain. “There was definitely a stigma,” says Johnson. “People were vying for who was going to be the best academic. Fantasy was not taken as seriously.”

Still, few of them were lugging around a massive trilogy. “He was the novel guy,” says Johnson. “He was always asking people to read it and give him feedback.” He would print it out and make copies at the Pullman Kinko’s, bind it with a black plastic binding, and then pass it around. “Nate [Taylor, Johnson’s roommate] read it. Nate’s dad read it. Tom [another friend] read it. One of his English 101 students even,” he says. “You knew that he cared about it desperately.”

The book was different, engaging, and “he writes jokes. That’s a really rare treat in fantasy,” says Johnson.

“Books are a poor substitute for female companionship, but they are easier to find,” Rothfuss writes in The Wise Man’s Fear.

Rothfuss lived in the world of the book. When he wasn’t writing, sometimes he and his friends would play in the world—a role playing game similar to Dungeons and Dragons. “This was serious geek business,” says Johnson. “Pat’s world was so sophisticated and so nuanced.”

Rothfuss guided the players through adventures in the realm he had invented. “It allowed him to think about his world as a real place,” says Johnson. He created money, had sorted out the crop rotations, devised languages, cultures, and folklore. They spent time there and could try out different ideas. “We got to play in his sandbox, so to speak.”

While attending graduate school, working on his book, and hanging out with his friends, Rothfuss was also struggling to find an agent or a publisher. In his words, his writing was “rejected by roughly every agent in the universe.”

The name of the windfall

But then in 2002, a short story that Rothfuss had excerpted from his trilogy won the L. Ron Hubbard Writers of the Future contest. He was invited to Hollywood to accept his award at a ceremony. “He was so excited,” says Johnson. “He bought a tuxedo for the event.” Thanks to the award, “The Road to Levinshir” caught the attention of several book agents and ultimately led Rothfuss to DAW Books, a science fiction and fantasy publisher headquartered at Penguin Group.

After graduate school, Rothfuss returned to Stevens Point, settling into a life with his partner Sarah, teaching at the university part-time and writing. Once he sold his first book, his life changed, though his tastes didn’t. “Now I get to eat Chinese food whenever I want,” he says. “I can afford it.” He paid off his credit cards, bought a house with Sarah, and started thinking about other uses for his money.

The Name of the Wind got off to a good start, winning the 2007 Quill Award for Science Fiction/Fantasy/Horror and making the Publishers Weekly list of best books of the year. And it was getting great response from the sci-fi/fantasy world. Author Anne McCaffrey blurbed: “This is a magnificent book, a really fine story, highly readable and engrossing. I compliment young Pat. His first novel is a great one.” And a Times of London reviewer wrote, “I was reminded of Ursula LeGuin, George R. R. Martin, and J. R. R. Tolkien, but never felt that Rothfuss was imitating anyone. Like the writers he clearly admires, he’s an old-fashioned storyteller working with traditional elements, but his voice is his own.”

Hundreds of readers were turning out for each stop on his book tour, many of them also following Rothfuss on his blog. Rothfuss realized he now had some influence. “I got all this enthusiasm. I thought maybe I could make it mean something,” he says.

In 2008, while in the thick of editing his second book, Rothfuss started a project he named Worldbuilders to raise money for Heifer International, an organization that uses donations to supply families in needy countries with livestock like chickens, rabbits, and sheep. “It’s all about hope, it’s all about self-reliance,” he says of the nonprofit organization. He blogged that if his fans donated to Worldbuilders, he would match every dollar. “I pictured raising $5,000,” he says. “But we hit $5,000 in the first three days.”

He offered signed books and maps for the Four Corners world as incentives to fans supporting the project. By the end of that first fundraiser, the group raised more than $50,000. Great for Heifer. Not for Rothfuss. “It completely wiped me out,” he says. “And I had forgotten as an author, they don’t take taxes out of your money.” For a moment, Pat’s bank account looked dire. Broke college student dire. But then out of the blue, “I got a royalty check from Germany and that like saved me,” he says. He decided to keep Worldbuilders going.

Now in its fourth year, Worldbuilders is supported by a number of science fiction and fantasy writers, artists, and publishers. They donate books, t-shirts, calendars, and other things and the fans contribute cash. To date, the effort has raised more than $1 million for Heifer.

With the books, the conventions, the fundraisers, the family, and the fans, Rothfuss says his life is now pretty full. “Yeah, it’s pretty cool to be famous,” he admits. “But it gets to a point where it’s weird.” He misses things about his pre-published self. “I was way happier poor in college.” He turns wistful. There were fewer people dependent upon him for their happiness. And he nearly lost something that was crucial to his creating the books—that old Spartan environment he had as a student when the only important thing was his story. “I like isolation. I like quiet,” he says. A few years ago he bought a house in which to write, an old two-story former student rental away from the comforts of home and of friends and family. “I put a desk in there and instantly my writing productivity went up by a factor of 10,” he says.

That lasted for a while. Now, thanks to Worldbuilders and some of his other endeavors, the writing house is a lively zone. His employees helping with the fundraisers and managing the business of letters, bills, and special projects fill the house with life and noise. He fights the distractions by making his second floor office sacrosanct. “Nobody goes in that room,” says Rothfuss. “If the house is on fire, I will smell it. Thank you.”

The Wise Man’s Fear trumped the first book’s success. In March of 2011 it was #1 in hardcover fiction on The New York Times bestseller list. When he posted about it in his blog, in true low-key Rothfuss fashion, he told his followers that he would celebrate with some macaroni and cheese and, since Sarah and Oot were already asleep, an evening playing the video game Dragon Age II.

As he starts revising The Doors of Stone, he must first reread the previous two books so they are fresh in his mind. “There are some scenes and I forget that I wrote them,” he says. The fault is in the sheer length of Kvothe’s story. “I wrote my three books thinking it was kind of one big really absurdly long book,” he says.

Now he revises, reinvents and, as a distraction, concocts short stories. The third book is coming, he promises, maybe in two years. Maybe three. Maybe a hundred.

And then, there will surely be more stories set in this world, he promises. “The smartest thing I’ve ever done is keep writing.”

Rothfuss’s first book, The Name of the Wind, has found readers around the world. His second, The Wise Man’s Fear, was #1 in hardcover fiction on The New York Times bestseller list in 2011. Courtesy DAW Books

Web Extras

Tribble Trouble – a walk through the Icons of Science Fiction museum with Paul Brians

Reading in the Genres – Paul Brians opines about where to start.

A Nate Taylor (’02 Fine Arts) sampler

What is your literary taste?

Do you like detective stories? Or maybe you lean toward a historical romance? Or perhaps you’d like to escape into an adventure novel?

“Mysteries, westerns, women’s romance, horror stories; these are all genres,” says WSU professor emeritus Paul Brians. An expert in science fiction set in the post-nuclear holocaust world, Brians can also lend insight into how we got from early literary movements to our current fiction genres.

In his class notes on “Realism and Naturalism” (part of a Humanities 303 class), Brians delves into a variety of works of literature to explain the development of genres. The old-school romance—not quite like the steamy romances of today—is typically a compelling tale with exciting settings and fabulous plots, but few descriptive details.

“If you read Jane Austen,” says Brians, citing Pride and Prejudice, “ you may see that Darcy is devastatingly handsome, but you get no picture of what he looked like.”

Realism came as a response to romanticism. Authors like Honoré de Balzac, the grandfather of realism, changed the focus from the ideal to the everyday. His La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy) is thick with specific details of life, clothing, and possessions. “His attention to detail was obsessive,” notes Brians.

From Realism came Naturalism, a movement that took place in the late 1800s and into the 1940s and had characteristics of meticulous detail and a focus on environment. Émile Zola’s Germinal offers a story of a coal miners’ strike in Northern France. Life there is harsh and gritty. Naturalism is a fascinating trip, says Brians, starting with Zola and ending with the grittiest of genres, the detective novel.

The horror story has its roots in the gothic novel. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with its hideous monster might fit into the Gothic or horror genre, but think again, says Brians. The monster is created with technology—electricity. “That makes it science fiction,” he says.

Linda Russo and Buddy Levy of the WSU English Department have been dipping into these genres with their creative writing students. Sampling fantasy, horror, mystery/crime, romance, adventure, and westerns, Levy asks his class to not only try reading in these genres, but to take a shot at writing in them.

“Narrative is so ingrained in our culture,” says Russo. “It’s almost like they’re so comfortable in it, you almost have to bump it up into a craft.” So her students take things apart, looking at what goes into a story. She has them do exercises in realist microfiction, pieces of up to 1,000 words that exercise their descriptive skills, building scenes, and crafting characters.

When exploring literary genres, there’s a lot out there to like, says Levy. As a reader, he has generally followed a diet of “Capital L literary fiction,” he says. “But this class has taught me to loosen the reins.” Often teachers, and readers, get stuck in one area. But they’re missing out on works like the post -modern science fiction of Philip K. Dick, a fantasy like J.R.R. Tolkien’s, or the mysteries of Elmore Leonard and Dennis Lehane.

Good stories with strong characters and gripping plots are, even though they may be locked into genres, awfully good reads. “What we’re really talking about is the quality of the work itself. Just look at Cormac McCarthy and the western,” he says. “Blood Meridian. That may be one of the highest levels of literary skill.”

The Princess Project

Patrick Rothfuss dreams up a lot of projects. Some of those dreams (or nightmares) come true.

The Adventures of the Princess and Mr. Whiffle: The Thing Beneath the Bed (Subterranean Press) got its start as a bedtime story that Rothfuss concocted for his girlfriend Sarah while in graduate school at Washington State University.

It’s the tale of a little girl who lives in a marzipan castle with her teddy bear Mr. Whiffle. In the first telling of the story, Sarah didn’t really like the ending. So Rothfuss tried again, making it a bit darker. Then he told a third ending, even darker. So dark that Sarah couldn’t get to sleep.

In many ways, it is an old-school fairy tale of the Grimm persuasion, dark, scary, and without a happy ending. It’s more for adults, Rothfuss cautions. “There’s something inside us that really wants to hear about the wolf in the woods.”

The next day, he retold the story to his friends. They loved it.

“Right away, I started picturing the princess,” says Nate Taylor ’02, an art major who lived next door to Rothfuss and years later would draw the map of the Four Corners world printed in Rothfuss’s novels.

Over the years, the notion of a princess book would come up, but Rothfuss, who was back in Wisconsin, was too busy with his novels to focus on it. Finally, after the first tome of the trilogy was published, Rothfuss sat down to work up a proper script. With that in hand, Taylor, now an illustrator in the Puget Sound area, fleshed out drawings of the little girl and her world, her castle, and her bedroom.

“I wanted to make it very cute, to accentuate the ending,” says Taylor. “The characters all have big eyes and big hearts.” He embedded little clues along the way to the story’s ending.

For someone whose second novel contains 152 chapters, The Princess is surprisingly brief. But it packs a punch. “It has gotten chuckles from everyone that I’ve ever shown it to,” says Taylor. “Except for my parents.” They laughed nervously and then asked, “What did you do?,” says Taylor.

The book has now had three printings and sold around 7,000 copies. The publisher released it in limited hardback edition last December as well as in paperback before the end of the year. It’s something of a dark and delicious bonbon—with a bite at the end.