Photography Jian Yang

A Chinese native who was born during the Cultural Revolution, Jian Yang ’08 found his artistic self somewhere in between his home country and the United States. That understanding of the in-between is perhaps why, on a visit home after spending some time here in graduate school, he discovered a fascination for the disappearing tradition of rural Chinese opera.

Fine Arts graduate Jian Yang ’08 knows all about the in-between. As a photographer he lives in a world between the subject and the viewer. And through his art he focuses on almost-forgotten spaces and things: abandoned farmhouses, empty barns, railroad tracks, broken toys, dead animals on the side of the road, and empty chairs. Understanding the in-between is perhaps why, on a visit home after spending some time here in graduate school, he discovered a fascination for the disappearing tradition of rural Chinese opera.

From childhood, Yang was aware of Chinese theater. But it was something more for his parents, he says. “To me it was just traditional stuff. I had not much feeling for that.” His father played an instrument, the erhu, that’s used to accompany the performers. “Now I regret I never tried to learn it,” says Yang.

During his visit he caught a poorly-attended performance at a Buddhist temple. He was captivated. The stories, elaborate costumes, and ritualized performances charmed him. “Finally, I understood why my parents liked it,” he says.

Chinese rural theater comes from several thousand years of tradition, says Yang. Small troupes of actors would travel the countryside, stopping in towns and temples to perform during religious holidays and festivals. Their careful makeup and bright costumes denoted the type of character they played—villain, lover, clown. For many in the small villages, in a time of no television and few books, they were a chief source of information and entertainment.

The rural operas had some things in common with the better-known Beijing or Peking operas. At the same time they were more folksy enterprises, with many of the actors performing when they weren’t needed for agricultural work. The story lines are mostly from Chinese history—the tale of a general going to war or a well-known romance. It’s not unlike Shakespeare, where the stories are already widely known, says Yang. The operas are sung, often with instrumental accompaniment.

The opera, and in fact all types of traditional Chinese music, disappeared or was subverted in the 1960s during the Cultural Revolution when any cultural work that did not support the ideology of the communist leaders was banned. Fortunately it was only a decade-long hiatus. The operas had a revival in the 1970s after Mao Tse-Tung died. For years they continued to be popular in the villages and towns where the actors toured.

“But now, nobody cares,” says Yang. People his age and younger are too focused on western culture, rock music, and contemporary art. Without their interest, fewer new artists are learning the traditional art form and fewer will carry it on. Now he feels driven to record it before it vanishes altogether.

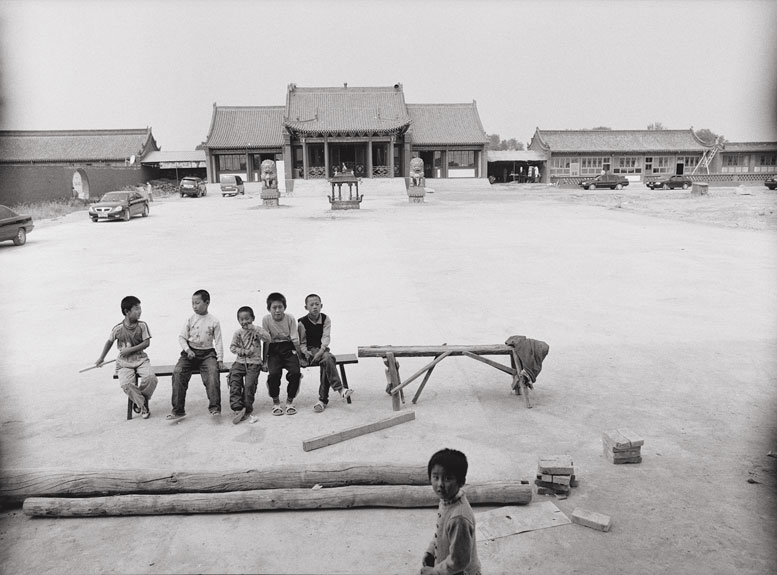

A friendship formed back in China has opened the rural theater world to him. Yang met a Buddhist monk who managed the Wenshu Chansi temple in the area of Huai Ren. The two liked each other and the monk invited Yang to become one of his students. He also opened the temple, a large complex that during traditional festivals serves thousands, for Yang to photograph. They agreed to the project with the hopes that in documenting the life and sights of the temple grounds, they might share the culture with others.

When he was last in China, Yang met the members of a Chinese rural opera company, a touring group of actors and musicians. At the temple with the monk’s permission, Yang shot black and white images of the troop with his Mamiya medium-format camera. He captured their live performances as well as the scenes backstage.

The troop is usually at a location for a week to 10 days. When they’re booked at the Wenshu temple they live and sleep there. “There are always empty rooms,” says Yang. “There’s also a kitchen where they can make themselves food.”

This particular troop warmed to Yang, pleased at his interest in their work. They let him photograph them getting into costume, resting after performances, and waiting behind the curtains for their cues.

The troop rarely drew a crowd. Many times, they were performing only for the older members of the community, those who remember seeing the operas as children, before the Cultural Revolution.

Too often, they performed without an audience, says Yang. But whether there is an audience or not is irrelevant, he adds. The actors are first performing for Buddha’s pleasure.

Because the popularity of traditional Chinese opera is waning, the actors all have to supplement their income. One actor and his wife own a small restaurant, says Yang, which they close during the theater season.

Yang’s efforts photographing the troupe have resulted in a collection of beautiful, somewhat haunting photographs: a trio on stage, a near-empty audience, an actress touching up her makeup, an actor having a snack.

He’s caught something in between the past and the present, a precious tradition in a precarious state.

I want to go back and shoot again, says Yang. “To me, this is just the beginning.”