Visiting China’s cities in recent years is like watching time-lapse photography. Consider: the city of Shanghai had one skyscraper in 1985; now they are legion. In 1988, I looked from Shanghai’s famous Peace Hotel on the Bund to the far side of the Huangpo River: nothing but a gray stretch of grimy shoreline. In less than 20 years, Shanghai’s Pudong District transformed from a forlorn swamp to something like the Chicago Loop. To say no more, this kind of construction explosion doesn’t afford much time to evolve a coherent architectural style.

The 20th century was a tough one for China. It began with the collapse of the Ching Dynasty in 1912. It then slogged through a failed attempt to establish a republic, a brutal war with the Japanese, a civil war leading to the ascension of Mao Zedong, several “great leaps forward” which proved to be great leaps backward, and a Cultural Revolution that erased an entire generation of intellectuals. And that only brings us to 1976!

Because of this political strife, the last century represents a large gap in the development of an indigenous architectural style in China—just at the time when the seeds of the Industrial Revolution bore fruit in the mega-cities and machine-like expressions of Modernist architecture elsewhere in the world.

Under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980’s, conditions began to change. China gradually privatized businesses and embraced international trade. Known as “capitalism with Chinese characteristics,” this new free-market attitude quickly led to an architectural renaissance in the urban centers. But this rebirth did not draw from indigenous architectural references. Much of it is imported from abroad, and from a variety of sources. The result is a hodgepodge of “looks”—think of it as a kind of architectural chop suey—which is at once stimulating, jarring, and, frankly, kitsch.

In traveling the country over the last 17 years—from Beijing in the north to Kunming in the south, from Shanghai in the east to Lhasa in faraway Tibet—I worked up a list of the ingredients for this architectural chop suey; I’d like to share that recipe here:

Western Classical

The Chinese have always been fascinated with things Western. Heaven is not only above, it may also be somewhere in the West. It is said that the sage Lao Tzu, the reputed founder of Taoism, did not achieve true sage status until he was allowed entrance into the Western Paradise.

This love for things Western crops up in many guises in China’s new urban architecture. One is the use of classical Greek and Roman forms, which, in the middle of a Chinese street, make for great moments of out-of-place architectural whimsy. Shown here (right) is the Beijing branch office of the Shanghai Pudong Development Bank. The gaps in the folded sheet metal cornice of the pseudo-classical façade speak to the quality of the construction.

At larger scales, the Western classical influence is much more “in your face.” Shown here (below) is a major government center in Chengdu, Sichuan Province (home to the Giant Panda). The building looks like a cross between St. Peter’s in Rome, the Capitol of the United States, and perhaps a rejected design for a Las Vegas casino.

Soviet Blocks with Capitalist Characteristics

Another feature of current urban Chinese architecture is what I call Soviet Blocks—but with a twist. The Soviet Union played a large role in birthing Communist China. It was a consultant to her politics; it also influenced her architecture. The 1917 Russian Revolution produced a style called Soviet Constructivism. It stressed the impersonal strength of steel and concrete, the machine as a personification of the utopian state, and mass housing for workers. In its early days the movement inspired some innovative forms, but the pragmatic outcome was blocks and blocks of anonymous boxes.

China’s population is currently around 1.3 billion, almost five times that of the United States. Mass housing blocks are therefore a necessity in China; you see them everywhere, and at densities rarely found in the U.S. But what makes the newer ones noteworthy is that they are a mix of the original Soviet mass housing, which expresses impersonal collectivism, with something that must look attractive, which is an outcome of capitalist investment. After all, new housing in China is not government issued; you have to buy it, and for a pretty sum at that.

The result is something like this (above) in Jinzhou, a city near the new Three Gorges Dam area. The development retains the anonymity of block housing. But it also has a sheen of the picturesque. The white walls and colorful roofs hark back to the color palette of historic Chinese architecture in this region. The balusters along the water and the arched stone bridge look like they came out of an emperor’s garden. I call this housing Soviet Blocks with capitalist characteristics.

Block-ism

Soviet Blocks are different from just Block-ism. The common features of Block-ism are buildings comprised of, well, large oversized blocks. They have a simple-minded toy building-block quality to them. Often the blocks are juxtaposed in unsubtle and ungracious ways; these buildings invariably look brutish. I think of them as building blocks on steroids. Here (right) is a blockish-brutish hotel in a city named Dazu in central China; note the Darth Vader-like penthouse.

This blockish look can be found in any Chinese city. In my view, Block-ism comes out of several factors. One is total discontinuity with China’s architectural past. The other is the attempt to connect with the international architectural scene. These monolithic forms, then, represent an attempt by Chinese designers to engage in the Modernist conversation they were excluded from for most of the 20th century. But these designers did not benefit from original participation in the gestalt of Modernist design as truly a cultural phenomenon of a machine age. The result is this artificial Block-ism.

The Chinese Hat Syndrome

For millennia Chinese architecture has typically been of one-story construction. Hence it is horizontal more than vertical, resonating with the lay of the land in a historically agrarian culture. The enduring signature of this horizontal architecture is the Chinese roof. The Japanese commentator Ju’nichiro Tanizaki likens this roof to an elegant canopy suspended from the sky. The subtle curves of the roofline resolve in upturned eaves, which gracefully shed the rain while allowing sunlight into interior recesses.

The Chinese roof is one element which has survived the tumultuous 20th century. Neither Marx nor Lenin nor Mao, nor laissez-faire capitalism, has succeeded in erasing the memory of the Chinese roof. And this finds expression in two ways in the current building boom. One is simply plopping the roof down atop any building, of any size, at any location. I call it the Chinese Hat syndrome. Here (right) is the Ministry of Communications building in Beijing, and here (below right) is new housing in Chengdu. Both these pictures show vertical buildings, and yet both sport Chinese hats. This is no longer about shedding rain; this is all about reminding one’s self that one is, after all, still Chinese.

The other way the Chinese hat syndrome is expressed is much more significant—in fact it may be one harbinger of any genuine indigenous style yet to emerge. It is this: new Chinese buildings have an irrepressible urge to resolve themselves with organic forms at the roofline. These gestures are almost always nonutilitarian. Yet they are relatively expensive to build.

Look at this building (below) in Shanghai: the organic forms are over two stories above the rooftop levels, and compared to the windows of the individual housing units, they are enormous. Again, this is not about shedding rain. This is a contemporary manifestation of the historic organic Chinese roof, now rendered a decorative gesture. The prevalence of organic forms atop tall buildings in China—and maybe some of them, like this one, are more scarf-like than hat-like—is truly a unique feature of new Chinese architecture. The next time you’re in China, take note of those hats and scarves, because they come from a long stylistic history.

Object fixation

Another tendency in contemporary Chinese urban architecture is fixation on the building as an object. One must understand a tad of Chinese philosophy to appreciate this. The Chinese worldview sees all individual units as parts of larger organic wholes. Certainly this applies to individual persons; but it also applies to individual objects. Everything is a piece of a larger fabric of nature. In this worldview nothing individual is to stick out; everything must conform to larger patterns. As a matter of fact, one reason why there is no formal tradition of architectural theory in China is because buildings were never conceived of as distinct objects worthy of contemplation in their own right.

Not so now. One result of the influx of Western ideas into China is fixation upon single buildings as individual expressions—often quite independent of what is going on around them. The new Shanghai Museum (above, right) is built to look like an ancient Chinese ritual vessel, complete with handles. Not to be outdone, a department store on a Chengdu street corner is built to look like a cruise ship, complete with anchors.

This look-at-me individualism does not come from native roots. It is imported. And this fact, in conjunction with lack of a theoretical tradition to guide how these objects should look, results in all sorts of amazing forms.

Postcard Chic

The Chinese have always had a thing about travel. We already saw how Lao Tzu traveled west to achieve sagehood. Also, Chinese Buddhism encouraged travel because it was one way towards enlightenment. Even during Mao’s disastrous Cultural Revolution, an unspoken benefit for those young Red Guards wreaking havoc all over the country was that they got to travel anywhere—for free.

The point is this: because the average Chinese has historically been so place-bound, the faraway has always seemed magical. Not surprisingly, this is reflected in the new architecture. Here (right) are nouveau riche housing units along a freeway on the outskirts of Hangzhou, a large city near Shanghai:

What is going on here? Gingerbread trim, vaguely Victorian gables, steeple-like roofs, a widow’s walk, colors reminiscent of the painted ladies of San Francisco, and on and on. I call it Postcard Chic; it’s a grab-bag of different motifs from faraway places. Greetings from Hangzhou! Wishing you were here! Or more accurately: wishing I am anywhere but here!

A Great Wall

China today is certainly not walled off to the outside world. But that does not mean the Chinese worldview has been liberated from what I call a wall mentality. Again, a small dose of Chinese philosophy: in the classical Chinese worldview, everything inside the wall is family, while everything outside the wall is not-family. The traditional Chinese courtyard house is surrounded by a wall. Chinese cities were also always walled. Go to China today and company headquarters, schools and universities, apartment complexes, parks—all tend to be surrounded by walls. And then, of course, there is the Great Wall. The Chinese pictograph for “country” is a four-walled pattern, as is the pictograph for “garden.” The wall is an enormous factor in the Chinese psyche.

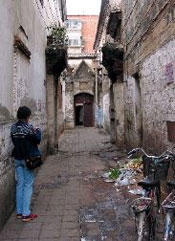

My point is that this wall mentality is not conducive to the generation of coherent urban plans. It most negatively affects “in between” public spaces: sidewalks, plazas, green spaces—in short, spaces that, precisely because they are publicly shared, do not fall “within the wall” of any family identity. Shown here is an alleyway in a residential district of Kunming, in southern China. Note the garbage simply dumped against the wall. Now, granted, this is not a new area of Kunming, nor is it a wealthy one. But the truth is that this picture, alas, is quite representative of a larger attitude towards public spaces. And Chinese cities suffer because of this. Consider: in a country that has valued oneness with nature for millennia; Chinese cities today are some of the most polluted in the world.

In sum, all of these ingredients make for a new and energetic, if not frenetic, Chinese urban architecture. Among the stylistic ingredients are architectural themes and gestures from all over the world, and they mix with the historic Chinese experience to produce, let us say, a new kind of architectural chop suey.

View an exclusive audio slide show featuring David Wang talking about the often undirected and chaotic proliferation of architectural styles in today’s China.