Joe Monahan, from all appearances a typical American frontiersman, arrived in Idaho Territory in the late 1860s. He was lured by the promise of fortune in the hillsides and settled in Owyhee County, which The New York Times had described as “a vast treasury” with “the richest and most valuable silver mines yet known to the world.”

Monahan built a cabin and mined a claim. He also worked as a cowboy with an outfit in Oregon.

When he returned to Idaho, he settled into a dugout near the frontier town of Rockville. An 1898 directory lists him as “Joseph Monahan, cattleman.” And his neighbors described him as slight, soft-spoken, and self-sufficient. Monahan embodied that classic notion of the western settler: rugged, moral, and hardworking.

But when he died of pneumonia in the winter of 1904, another, altogether different, description surfaced.

Those who ministered to Monahan’s remains discovered the body of a woman beneath the rancher’s clothes. The news flared across the country in newspapers carrying varied accounts of his life. Monahan may have been from Buffalo, New York. Monahan may have started dressing as a man for safety and moved west to find work. And he lived in disguise for more than 30 years.

To a degree, Monahan’s tale has endured. But when it comes to such transgressive behavior in the West, says historian Peter Boag, the story is far from unique: “Cross-dressing was pervasive.”

Monahan’s tale may be emblematic of the West—that what we see on the surface might be quite different from a more complicated truth beneath. And the hunt for the true stories of the American West can lead into intriguing territory.

In one case, an architecture expert leads his 40 students to the heart of San Francisco to discover the real history of Chinatown. In another, a Japanese photographer from more than a century ago gives us a fresh view of life on the frontier. Adventuring into places such as these, we can discover a new Western reality.

As WSU’s Columbia Chair in the History of the American West, Peter Boag pioneers new territories—including that of sexuality and gender in Western history. Telling Monahan’s story and seeking other examples of Western cross-dressers, he discovered more and more instances of cowboys not being boys, and ladies with layered identities.

In his book Re-dressing America’s Frontier Past, Boag introduces us to Eva Lind, a waitress at a hotel in Colfax, Washington Territory. He found Lind’s story in an 1889 edition of the Rocky Mountain News. Also known as Phil Poland, “she” was able to work for a considerable time as a woman. In Lind’s case and others, Boag found they were much a part of daily life in their communities.

When Harry Allen was arrested in a Portland, Oregon, rooming house in 1912, he was living with a known prostitute. The police soon discovered that Allen, who had also lived in Seattle and Spokane, was notorious around the West for crimes including selling bootleg whiskey, stealing horses, brawling in saloons, and, to the suprise of his captors, cross dressing. Allen, they learned, was anatomically female and also known as Nell Pickerell.

“There were lots and lots of women who dressed as men,” says Boag. “And as I kept looking I found a surprising number of men who dressed as women.”

But the truth of it has been much concealed by a mythology of the American West, a broad bright notion of a wholesome, hyper-masculine place that spread across the Western horizon in the early 1900s, and was reinforced by scholarly work, dime novels, Wild West shows, and Hollywood. It obscured many of the more complex and confusing truths about our history.

The myth of the West, according to many historians, took hold in 1893 when Frederick Jackson Turner first advanced his “frontier thesis” at the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago. The frontier line, Turner informed his colleagues, was that place out West that was “the meeting point between savagery and civilization.” It was a free space where man met nature and where our national character drew from the “restless, nervous energy,” of the frontier and the “dominant individualism” of those who ventured there.

But the tales of the rugged individualists of Turner’s West, the pioneers who overcame great odds and defeated Native Americans, as well as the cowboys, miners, and fur trappers, served to cover over more troubling stories of those men who don’t seem to live up to the cultural idea of being “real men,” claims Boag.

“The same goes with women,” he adds. “Though it’s a little bit easier for us to accept in our culture, in our history, women who take on men’s roles. We can say they dressed as men for safety, to escape something, or to travel more easily.”

Indeed the myths of the American West carry a certain truth, but they are in many ways less than the real stories, says Boag. “I’m fascinated with how these myths have been used in our culture to obscure more complicated, more difficult, more troubling, and therefore what I think to be the more interesting human stories of our country and the region,” he says. “I’m fascinated by what we remember, what we forget, and why we forget.”

Perhaps the frontier lured these transgender people, says Boag. They, too, bought into the promise of freedom and opportunity. Maybe they believed they could remake themselves in this new, undeveloped place. In many cases these cross-dressers and transgender individuals lived and even thrived in the new territory.

That Joe Monahan was a woman came as no surprise to his associates. He was small, he had no beard, and, according to one newspaper account, had “the hands, feet, stature and voice of a woman.” Boag found a census form filled out by an Owyhee County neighbor. Next to Monahan’s name, the neighbor checked the box for “Male” but also wrote in a comment: “Doubtful Sex.”

“It’s not so much that people were enlightened,” says Boag. “But these (cross-dressing) people had a role in their communities. They were accepted, sometimes begrudgingly accepted.”

THE CULTURE OF THE COWBOY

The mythical West is a setting of “restorative masculinity.” A century ago, tales of men like Daniel Boone and Kit Carson found reinforcement in the scholarly histories of Turner and his contemporaries, the art of Frederic Remington, and the novels of Owen Wister and James Fenimore Cooper. Their westerner was white, male, courageous, healthy, and heroic. And usually atop a horse.

In the 1880s, Theodore Roosevelt, exemplar extraordinaire of “restorative masculinity,” set up a dude ranch in the Dakota Badlands where, after countless hours hunting and on horseback, he transformed himself from a New York weakling teasingly called “Jane-Dandy” by his fellow assemblymen into a robust cowboy-soldier on the path to become the nation’s leader.

Men in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries seemed to crave models of masculinity—gun-slinging heroes, masters of their own fate, and men at home in nature, Boag contends. This new man dwelt in the West, a pure place of natural wonders and healthy living. He was armed with a code of conduct built out of the elements of survival. By the 1920s and into the Depression, the mythic West offered an “other” view of America, away from the factories, rail yards, and city grime.

“The old myths are so hard to eliminate because they speak to a simpler time. They speak to certain cultural ideas,” says Boag.

But in the late 1960s a new wave of historians started wrangling with these notions. Viewed through the fields and ideologies of feminism, ecology, ethnic studies, and civil rights, the old histories came across as stilted, racist, and oversimplified. Scholars found

new approaches to revisit this chapter of American history with fresh ardor.

In the 1970s, WSU’s Sue Armitage ventured into the untrammeled territory of women’s Western history. She explored the woman in the old West myth and found three distinct stereotypes: the refined lady, the helpmate, and the bad woman. Writing in The Women’s West, she identified schoolteachers and missionary wives as the “ladies” who never fully adapted to the West. On the other hand, the helpmates or the farmwives did adapt. They were hardworking and moral but quickly took a back seat to their male counterparts. Finally, she found the bad women—the prostitutes and opportunists who may have had some success or power, but who usually met an unpleasant end. Overall, the women of the mythical West are “incidental,” and “unimportant,” she concludes.

Armitage then explored the stories of real women outside the stereotypes, for example the single woman homesteader (Joe Monahan might fit this category) and the unwilling helpmate who didn’t relish life on the frontier. She and her colleagues uncovered a West that was far from the male-dominated, untamed, unpopulated, ethnocentric frontier it had been dressed up to be. And her work serves as a foundation for historians today who say even the notion of a “frontier” is false.

Broad and diverse communities of Indians populated the West, for a start, then came explorers, miners, fur trappers, and traders from all races. James Beckwourth, for one, was a well-known black mountain man. And Joe Monahan settled right in the middle of Owyhee County, named for three Hawaiian explorers. In 1987, historian Patricia Nelson Limerick offered an alternative view: the “American West was an important meeting ground, the point where Indian America, Latin America, Anglo-America, Afro-America, and Asia intersected.”

THE FRAUD OF CHINATOWN

Examples of the real West may sometimes be lodged within the myth. Last October, Phil Gruen led about 40 WSU architecture students to explore a fabricated past from a street corner in San Francisco.

In the late 1800s the city was divided into specific ethnic districts. Places like Chinatown even had their own guidebooks.

With his tour and with his book Manifest Destinations, Gruen, an associate professor in the School of Design and Construction, moves the notion of defining the West into its cities. Looking at Salt Lake City, Denver, and San Francisco, he explores the discrepancies between the images presented by the urban West and the truth. The early guidebooks to these cities focused narrowly on the time of European settlement, notes Gruen. They talked of “hardy pioneers” and missionaries overcoming adversity, and glossed over details that showed how diverse these settlements really were. And where the diversity was impossible to hide, the tour guides packaged it up to look “different” or “quaint,” making it intriguing to visitors.

“San Francisco’s Chinatown was a huge tourist attraction,” says Gruen. “It may have been the single most popular tourist attraction in all of the nineteenth century urban West.”

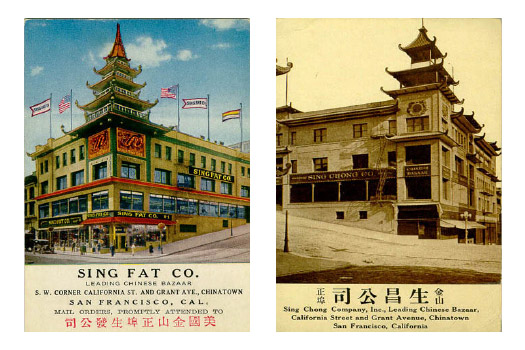

Gruen led his group through the green-roofed Dragon Gate and halted in front of what he deems two of the most significant historical structures in San Francisco: the Sing Chong and Sing Fat buildings. This neighborhood was built on racial discrimination and exploitation, he says. Beneath the charm is the true history, that the Chinese of San Francisco were sequestered within this nine square block area that they couldn’t easily leave, according to Gruen, “or they would be beaten or threatened.”

Western architecture filled the neighborhood, which was built for white residents in the earliest years of the Gold Rush. At the completion of the Central Pacific Railroad many Chinese workers headed to San Francisco even though the laws forbade them from living anywhere but Chinatown. “The architecture was not necessarily designed to look Chinese,” says Gruen. “But the residents decorated and designed where they could with lanterns and verandas and balconies.”

By the 1880s, more than 21,000 Chinese had moved there, more than 20 percent of the entire Chinese population in the country, notes Gruen. Because of restrictions, the residents made use of what they had, building into the streets and even the alleys. Though the neighborhood had been altered to serve the burgeoning community, it lured tourists with its lively markets, restaurants, stalls, temples, and even opium dens.

When the earthquake of 1906 and subsequent fire destroyed the neighborhood, and thousands of refugees relocated to tents in the Presidio, some of the city leaders saw an opportunity to push the Chinese out of San Francisco altogether. But others realized that losing Chinatown would cost them a tourist asset as well as tax revenue and trade opportunities. So, with the involvement of several Chinese merchants, the city’s white leaders rebuilt and reinvented the ethnic community.

Far from being true to a culture, “the Chinatown that was remade following the 1906 earthquake was a giant marketing scheme in the image of what urban elites wished for tourists to continue to see in Chinatown: a visibility of difference,” says Gruen. “Through design, they reinforced racial difference.”

They built in a “hybrid architectural style that only superficially resembled any actual buildings in China,” says Gruen. The massive Sing Chong and Sing Fat buildings are pure western constructions with a “chinoiserie” of Ming-style details like tiled roofs, pagodas, and “oriental” colors.

Far from authentic, these buildings nonetheless set the standard for the rest of the neighborhood. And they influenced the appearance of Chinatowns around the country, says Gruen. San Francisco’s Chinatown is still one the West’s biggest tourist attractions. But Gruen hopes his students and other visitors might see the history behind the designs—a history of race relations and politics.

PICTURING A NEW OLD WEST

We are still just at the threshold of exploring our Western territory, note Boag and Gruen. The powerful mythology continues to permeate our history. So how and where do we find new ways to understand our Western past?

In diaries, letters, newspapers, and photographs, to start. WSU has archived thousands of primary sources which historians today use to dig into a range of subjects from ecology to race relations.

A trove of glass plates and photographs from the Okanogan Valley’s frontier days reveal a more accurate picture of the American West than many of the old histories, guidebooks, movies, and novels. The works of Frank Matsura, a photographer born in Japan who moved into the valley in 1903, chronicle the end of mining in the area and the influx of farmers and families. In his 10 years as a valley pioneer, Matsura became a friend, neighbor, and trusted resource to the community. As such, he was close to and photographed many: cowboys, Indians, lawyers, teachers, waitresses, homesteaders, and cooks. He even knew a horse thief or two.

Matsura, himself, was an ill fit for the “traditional” notion of Westerner. He was small, Japanese, outgoing, and single. He had a lively intellect. Fluent in English, he once gave a public lecture about Japan during the Russo-Japanese War, and, another time, wrote an article for the local newspaper on the education of Japanese women.

As a WSU graduate student in American studies, Kristin Harpster spent nearly a year with Matsura’s photograph collection, organizing the materials and researching the man himself. She found that Matsura landed in Seattle in 1901 at the age of 21. He may have been aware of his failing health, and moved across the Cascades to work in a dryer climate. He took a

job as a cook’s assistant at the Elliott Hotel, a squat two-story whitewashed building in tiny Conconully.

The town was struggling in the decline of prospecting, notes Harpster. At the same time, the region was in the throes of rapid transformation, of new orchards, irrigation projects, and growing communities. Matsura spent his free time out with his cameras shooting town events and portraits as well as public works projects, eventually turning his photography into a full-time business.

In 1907 he opened a studio in Okanogan, a stand-alone building with clapboard siding and a striped awning bearing the name “Frank S. Matsura” arched over “Photographer.” He welcomed visitors, and by the record of his photographs, they were of all stripes.

He’d also step outside and record the winter festivals, Fourth of July parades, talent shows, and much of the daily life of the region. One picture features about 20 local bachelors perched on a railing on a Sunday morning waiting for the pool hall to open.

His images repudiated boundaries: Two cowboys, a white and an Indian, in full regalia pose playing cards together; Matsura and a townswoman sharing a tender moment with their heads bent together. In a series with a white woman, Matsura dons a woman’s bonnet and later appears to kiss his companion behind a hat. Another playful image shows him ice skating across a frozen Okanagan River arm in arm with a tall white man.

“His work is remarkable for its striking departure from the dominant understanding of frontier life that prevailed during the early twentieth century and that persists to this day,” writes Glen Mimura, an Asian American studies professor at the University of California Irvine.

Mimura and a few other scholars have contrasted Matsura’s work to that of his contemporary, photographer Edward Sheriff Curtis, who popularized a vision of the disappearing American West before the advance of industrialization. The two photographers offer significantly different visions of Native Americans. Curtis’s work is melancholy, what he claimed was a capturing of the Indian’s lives before they disappeared into the past. Matsura, instead, recorded a society in transition. Some of his subjects lived in the traditional teepees, but wore western clothes. Others built houses, routinely interacted with their white neighbors, and took part in the daily life of the towns. Matsura’s Indians were individuals, happy families, cowboys and cowgirls.

Curtis traveled with a trunk full of traditional Indian clothes to help his subjects look more “authentic.” Ironically, the clothes were not always true to the culture of the person he was photographing.

The Japanese photographer captured smiling Indian children in front of a teepee in their Sunday best, a Chelan Indian man in a bowtie, and Wenatchee and Chelan women and children on horseback in town for the Fourth of July parade.

“Matsura’s Okanogan world cheers the hell out of me,” writes Rayna Green, an American studies and folklore scholar and curator emerita at the National Museum of American History. “Yes, the land settlements were a mess, and yes, the homesteaders and the Army Corps of Engineers and the lumber mills and fruit companies took it all. But somewhere, in this world he shows us, Indians aren’t weird, heartbroken exiles, or zoo animals for the expositions, endangered species preserved forever in photographic gelatin.”

In 1992, Green published an essay titled “Rosebuds of the Plateau: Frank Matsura and the Fainting Couch Aesthetic.” She focused on a Matsura photograph of two Victorian girls reclining on a fainting couch. They are Indian.

“I like these girls. I am transfixed by this photo,” writes Green. “From the moment I saw it, hanging on the wall, surrounded by other photographs of Indians, contemporaries from the turn of the century, I loved it.”

She then considers Matsura’s other photographs. “His images of Indian ranchers and cowboys alone give us a better sense of what and who Indians were during those awful years after reservationization,” she writes. “They’re riding horses, playing cards, dashing off on posses with the sheriff, wearing those delicious angora chaps, beaded gloves, silk neckerchiefs, bear coats, and broad-brimmed hats.”

Curtis’s pictures of American Indians are beautiful, extraordinary, Green said once in a PBS interview. “For me though and I think for a lot of native people those pictures give us a lie, give us a fantasy. I want the real picture of a daily world the way native people were living it, and Curtis can’t give me that.”

Matsura was skilled, highly productive, and insightful. He leaves us an insider’s view of a richer, nuanced, and at times cheerful West.

When he died of tuberculosis in 1913, hundreds poured into town to pay their respects, noted the newspaper. His friends filled the auditorium and spilled out of the building.

His effects went to William Compton Brown, an Okanogan attorney who had set up practice just as Matsura had opened his studio. Just three wooden boxes contained the photographic prints and film and glass negatives that made up the body of Matsura’s work. Brown didn’t open them until 1954. When he donated his papers to WSU, Brown released hundreds of Matsura prints and postcards, all offering bright windows into Washington’s past.

The notion of the West as a wide open place now plays out in different ways. Fresh territory awaits historians and scholars. It may be more like the West that Matsura shows us, a place with humor and diversity. Or one that Gruen gives us through architecture and tourism, a more complicated story. And, as Boag shows us, it is likely filled with characters who may no longer be hidden in the shadows of the American myth.

“The Chinatown that was remade following the 1906 earthquake was a giant marketing scheme in the image of what urban elites wished for tourists to continue to see in Chinatown … The massive Sing Chong and Sing Fat buildings are pure western constructions with a ‘chinoiserie’ of Ming-style details like tiled roofs, pagodas, and ‘oriental’ colors.”

On the web

Crossing Boundaries: Portraits of a Transgender West at the State History Museum