John Mullan closed the last link of the Northwest Passage and vanished from history—until now

On a May morning in 1858, along a small creek on the northern edge of the Palouse, hundreds of warriors from several Inland Northwest Indian tribes closed in on 160 Army soldiers led by Col. Edward Steptoe. An Army retreat turned into a 10-hour running battle. Two company commanders were mortally wounded, panicking the men. At last, the troops took up defensive positions on a hillside in what is today Rosalia. As night fell, they were surrounded, outgunned, and down to two rounds of ammunition apiece.

More than a century and a half later, Keith Petersen ’73 is standing on the hillside, looking at a memorial to the battle. Frosted grass crunches under his feet. A set of displays illustrates Steptoe’s advance and retreat.

“This,” says Petersen, whose grizzled beard could put him in the nineteenth century as easily as the twenty-first, “came real close to being Custer before Custer.”

As it happened, Steptoe’s men muffled their horse’s hooves, buried their howitzers, abandoned their pack animals, and stole away under cover of darkness. Without a doubt, says Petersen, the Indians let them escape.

But as the spring of 1858 gave way to summer, a fundamental tension lingered like gun smoke in the morning air. The Indians did not want the U.S. government to build a road across their land. They had grudgingly agreed to the road in the 1855 Walla Walla Treaty negotiated by Isaac Stevens, Washington Territory’s first governor and supervisor of its Indian Affairs. But the treaty had yet to be ratified by Congress, making any road a trespass. Father Joseph Joset, a Jesuit missionary who had tried and failed to head Steptoe off from his ill-fated battle, later speculated that, had a road-building party been traveling across the Palouse instead of troops, it “would have been sacrificed.”

The road would come to play a pivotal role in the development of the Northwest, let alone the young nation’s aspirations. It would run from Walla Walla to Montana’s Fort Benton, an obscure-sounding route today, but the last link of the transcontinental Northwest Passage President Thomas Jefferson envisioned when he sent Meriwether Lewis and William Clark out west more than 50 years earlier. Stevens himself hoped it would be the route of a transcontinental railroad, positioning Puget Sound as the nation’s gateway to Asia.

“It’s always this drive of connecting, connecting the East and the West,” says Petersen. “That explains so much of nineteenth century American history, that connectivity between the East and the West. Well, you can say it still describes us.”

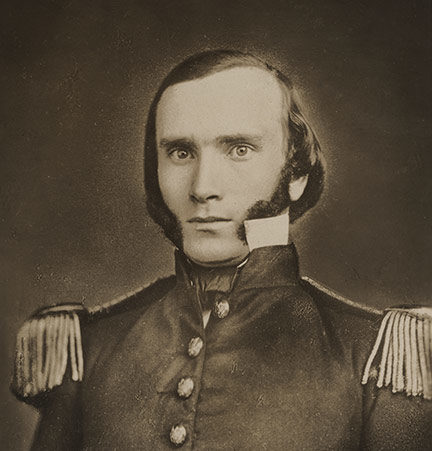

Leading the road’s construction was John Mullan, a brash, aspiring, indefatigable 27-year-old lieutenant. The son of an army sergeant who worked at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Mullan was educated at West Point, less a military school at the time than a first-rate engineering college and precursor to the land grant college. Here graduates were outfitted with “science for exploring the hidden treasures of our mountains and ameliorating the agriculture of our valleys.”

Steptoe’s Disaster, as it came to be called in some circles, was a linchpin in the development of Mullan’s road. Within months, the Army was back with a vengeance, clearing the way for Mullan to finish his road in a massive feat of frontier logistics, leadership, brute effort, bureaucratic wrangling, and frostbite. At which point he all but vanishes from the pages of history.

“It’s hard to pick up a book about Northwest history that deals with the nineteenth century and not find something in the index about John Mullan and the Mullan Road,” says Petersen, “but it just ends. He just totally disappears from sight.”

Petersen first heard of Mullan as an undergraduate history major advised by David Stratton, now an emeritus professor after a 51-year career at Washington State University. In 1986, he jotted his first notes on Mullan, “thinking someone else would surely write a book about this guy.”

But that someone turned out to be him. This May, WSU Press publishes John Mullan: The Tumultuous Life of a Road Builder. It’s the result of some five years of writing and research, including coast-to-coast travels and visits to more than two dozen libraries and archives.

“I literally had dreams about John Mullan,” Petersen says.

Along the way, he discovered a hard-edged embodiment of nineteenth century hubris and grit, a quintessentially Western tale of frontier aspiration, courage, checkered dealings, and bad luck.

Back in the late ’60s, Keith Petersen lived in Battle Ground, a town named for a battle that brewed but never quite boiled over. His high school history teacher, Bill Hill, in effect threw out the history textbooks, choosing instead to use local history to teach larger lessons.

“This was kind of cool,” recalls Petersen. “You could talk about Indians and the Sand Creek Massacre or whatever but all of a sudden you say, ‘the Army and the Indians got together out here where our high school is and almost had a fight.’ That’s pretty exciting stuff. It gives a whole new picture to things.”

It was a departure from traditionally dry, detached history. Along with stories from his long-lived grandfather, it showed Petersen that history could take many forms. Still, it would be a while before he would even realize that he might become some sort of historian.

When he arrived at WSU in 1969, advisors were assigned alphabetically. He drew Stratton, a western-raised and educated scholar who specialized in the American West and Pacific Northwest. Petersen had no particular major in mind, figuring he would take what he felt like and go from there. Come his junior year, when it was time to declare a major, Stratton looked at his courses and said, “I think you should declare it in history because that’s what you’re taking.”

So he did, and on graduation found employment working in a Vancouver sawmill. He spoke with Stratton about graduate schools, and on a visit to the University of Wisconsin, dropped in at the state’s historical society to ask about work.

“Can you start next week?” he was asked.

He worked there through graduate school and, along the way, realized two things: He liked public history, essentially the practice of history outside the classroom, and he didn’t need to get a doctorate to do it. Soon after he graduated with a master’s in history, Stratton told him about a job at the historical society in Latah County, Idaho, launching a peripatetic, 36-year career of researching and describing history in different ways.

As an independent consultant in the 1980s, Petersen did contract work for state and federal agencies, helping with interpretations, exhibits, and written materials. He wrote a history of the University of Idaho and the book Company Town: Potlatch, Idaho, and the Potlatch Lumber Company. He married Mary Reed, a fellow public historian he met at a mint julep social at McConnell Mansion, the Victorian home built in Moscow, Idaho, by William J. McConnell, an Idaho governor in the late 1800s. He spent most of the 1990s as an acquisitions editor for the WSU Press. With fellow Stratton student Glen Lindeman (’69 BA Political Science and History, ’73 MA History), they put out a dozen or so titles a year.

Starting in 1999, as the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial approached, Petersen acted as Idaho’s bicentennial coordinator, which segued into his current job, associate director and state historian for the Idaho State Historical Society.

And every now and then, John Mullan would drift across his consciousness. With the rise of the Internet in the late ’90s, he would occasionally search for information about him, taking a

dvantage of the web’s broadening reach into the world’s archival corners. Then, poking around the web in 2007 or 2008, he saw that Georgetown University had recently catalogued 13 boxes of Mullan papers stretching 8 linear feet. It was a eureka moment. He and Reed, his de facto research and editorial assistant, became the first people to go file by file through the archive, he says, “and that’s what made the biography possible.”

Not three months after Steptoe’s humiliation, the U.S. Army sought revenge. Gen. Newman Clarke, commander of the Pacific Department, brought in troops from most every post west of the Mississippi River. Putting Col. George Wright in charge, he said, “You will attack all the hostile Indians you may meet, with vigor. Make their punishment severe.”

Mullan could have waited things out in Walla Walla but, true to form, he smelled an opportunity. As a kid in Annapolis, the oldest of 11 children, he rounded up recommendations to West Point from political connections of his father, who served briefly as a city alderman. He then took the letters to President James Polk—the White House was a remarkably accessible place in 1848—and personally secured one of the president’s ten at-large academy appointments.

After West Point, he was assigned to a Pacific Railroad Survey led by Stevens and so impressed him that he was put in charge of what Petersen calls, “some of the most significant explorations ever undertaken in the West.” He scouted several routes to the Bitterroot Valley from the east, including the rugged, snow-driven stretch of Lolo Pass that nearly doomed Lewis and Clark.

When Wright set out to avenge Steptoe, Mullan had yet to see what would become of his road’s western section. So he signed on as the topographical engineer, or “topo.” This was no behind-the-lines clerk typist job. He was put in charge of 30 Nez Perce warriors. They wore Army-issue blue uniforms; Mullan, a model student at West Point but a free spirit in the field, wore buckskins.

The full force—600 soldiers, 100 packers and herders, and 1,600 animals—were lured into battle by a confederation of Inland tribes outside modern-day Spokane. This time the Army had long-range rifles, killing 17 to 20 Indians and taking no casualties over four hours. Wright singled Mullan out in his official report, saying he “moved gallantly.” For his part, Mullan barely notes the battle.

“He was right in the middle of it,” says Petersen. “He was leading the Nez Perce, the first people to engage with the enemy. This is exciting stuff. He comes back and writes his field reports that day and says, ‘Well, I think I found a wonderful place to put my road.’ He doesn’t say anything about the battle. It’s amazing. This guy was just monomaniacal about his road.”

Wright soon made that possible. A week after their first battle, the Nez Perce and cavalry soldiers captured a herd of 800 Indian horses. Over the next two days, Wright’s men slaughtered 700 of them. They also took to burning storehouses and caches and killing cattle in a path of destruction that anticipated Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s March to the Sea in the Civil War.

Coeur d’Alene and Spokane tribal members agreed to terms of peace. This included letting soldiers and settlers travel through the country unmolested. Other tribes were subdued by sheer intimidation. Over the course of the campaign, Wright hanged 16 Indians, including Qualchan, the son of Yakama Chief Owhi, who some say rode into Wright’s camp under a flag of truce.

“That immense tract of splendid country over which we marched is now opened to the white man,” wrote Lt. Lawrence Kip afterwards, “and the time is not far distant when settlers will begin to occupy it.”

Mullan immediately set about making his road happen. Taking an unauthorized leave, he traveled back to Washington, D.C., and with the help of Stevens, then a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, got an additional $100,000 appropriation from Congress. The following spring, he was back in the West, assembling a crew of 80 men and 180 oxen with a 140-man military escort.

An exultant Oregon Union predicted the road, “will open up a direct communication between the valley of the Mississippi and Oregon.”

The word “communication” is not accidental. Before the transcontinental telegraph and railroad, let alone the telephone and airmail, roads were central to communications. While Mullan was working on his road, a letter sent from Washington, D.C., in September did not reach him until January. To be marooned in Walla Walla, thousands of miles from the news of the East, was an antiquated, months-long version of life without WiFi.

What actually constituted a road was open to interpretation. The standard for Mullan was that it be 25 feet wide and capable of supporting a wagon.

“Those are the instructions that are given to Mullan,” says Petersen, “and it’s sort of like, ‘You know what to do.’”

From Walla Walla and up through the Palouse, the road was little more than the team’s tracks. The crew made the region’s earliest elevation measurements and compiled the first observations of longitude made above the continent’s 42nd parallel. A wagon-rigged odometer carefully logged the miles from Walla Walla, which were branded into posts along the road along with the initials “M.R.”

“Technically, the initials stood for ‘Military Road,’” Petersen writes, “but for most people the shorthand became ‘Mullan Road.’”

A private drowned crossing the Snake River—the only fatality of the project—but the men were tested in other ways as they skirted Lake Coeur d’Alene’s southern shore and encountered swamps, hills, boulders, tangled underbrush, and towering trees four and five feet thick. Mullan noted that the work, done with shovels, picks, saws, and black powder, was “more severe than I had any idea of.”

The crew made ferry boats of whipsawed lumber to cross the St. Joe River. They laid logs side by side for so-called “corduroy” roads across bogs. The Coeur d’Alene River required nearly 100 crossings and scores of bridges averaging 50 feet each. It rained all of October. November brought more than a foot of snow and sub-zero temperatures. Hundreds of the crew’s cattle, horses, and mules perished.

In December, as the temperature hit 40 below, the men built a garrison of log cabins and earthworks. They were 267 miles into their 624-mile effort and over budget. The Topographical Bureau wrote Mullan to say his expedition was disbanded.

But before he got the letter, Mullan sent Walter Johnson, a 23-year-old engineer, to Washington, D.C., by way of snowshoe, steamer, and Panama crossing to appeal for more funding. Working with Stevens, he secured a second appropriation of $100,000. It helped that Mullan nonchalantly reported that some of his crew found gold, otherwise keeping the discovery secret for fear the entire crew would bolt.

Work resumed in the spring, and on July 18, Mullan reached Mullan Pass, a summit he scouted six years earlier and the end of his slog through the Rockies. He arrived in Fort Benton on August 1.

In 1861, he set out on the road again, revising the early part of the route to go through today’s Spokane and north of Lake Coeur d’Alene. He repaired washed-out bridges, fell behind schedule, and endured yet another brutal winter. He finished in early June, but backtracking to Walla Walla, he was discouraged to see so much work undone by fallen trees and spring torrents. Still, historian William Turrentine Jackson wrote almost a century later, the Mullan Road amounted to “the federal government’s greatest contribution to transportation development in the Pacific Northwest.”

Returning east, Mullan married the well-educated, socially positioned Rebecca Williamson in 1863. The longest lived

of their five children was Mary Rebecca, or May, who married well and gave generously to D.C. institutions, including Georgetown University. While her father had personally visited James Polk, the eleventh president, to get a recommendation to West Point, May’s yard looked into the garden of John F. Kennedy, the thirty-fifth president.

When May died in 1962, her father’s personal and legal papers were donated to Georgetown. Forty years passed before they were processed and made available to researchers like Petersen.

The files were short on materials like letters from Mullan to his parents or wife, but they were loaded with materials from Mullan’s life after the road. With this as a solid core of information, Petersen and Reed scoured for historical tidbits across the country, visiting the Bancroft Library at University of California-Berkeley, the National Archives, the Maryland State Archives, Yale University’s Beinecke Library, West Point, and Chico State University. Archives in Idaho and Washington had information on people Mullan worked with or met while building the road.

“All of them have fragments of this story,” Petersen says.

In the Museum of North Idaho, Petersen saw the road’s most enduring blaze, from a white pine marked at Fourth of July Pass, so named for a celebration the road crew held on July 4, 1861. It marked the trail until 1988, when the tree was cut down. At the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane, he found a pistol donated by Peter Mullan, a Coeur d’Alene tribal member who claimed John Mullan was his father by way of a liaison with Rose Laurant, a Flathead woman Mullan could have met while scouting the Bitterroot Valley in 1854.

Idaho state historian by day, Petersen worked on weekends, evenings, and mornings on Mullan’s story. He wrote from 5 to 6 a.m., producing about a page a day for more than a year.

The result is a portrait of a deeply complicated, fascinating individual. Mullan was intensely loyal to his family, but willing to run roughshod over most anyone else. He was racist, but with flashes of respect for figures like Owhi, “a noble and generous Indian” he met in 1854. He was a remarkable leader, keeping his men moving and working and even cheerful in the most brutal conditions. He was bright but no genius, a “monster for work,” facing conflicts with a chief tactic of outworking his opponents. He was hugely egotistical, and, Petersen suspects, “pretty obnoxious.”

“The hard part for me on this one,” Petersen says with a chuckle, “and I don’t want to say this in the wrong way, is I wish I could have liked the guy a little better.”

His road work done, Mullan lived to be 79 before dying, broke, paralyzed, and bed-ridden, in 1909. He had spent some three decades struggling to capitalize on the West’s economic promise, repeatedly coming up short.

He had helped reconfigure Washington’s territorial boundaries, hoping to become a territorial governor, and was outmaneuvered by William Wallace, who became the first governor of Idaho. A last-minute appeal to President Abraham Lincoln was fruitless.

Resigning from the Army, he returned to Walla Walla, then the largest city in Washington, and was hired to build a short line railroad from the Columbia River. The scheme, writes Petersen, “quickly fizzled.”

He joined his brothers Louis and Charles on his Walla Walla farm and was soon squabbling with them over who owned what. His brothers Ferdinand and James joined in. Louis sued John and Charles. John sued James and Louis. The operation went broke and John went back east to Rebecca’s Baltimore home.

He won a mail contract for a stagecoach line between Chico, California, and mines in the Boise basin, but failed to raise enough capital to make the line work. The effort sputtered and died in less than two years, bankrupting Mullan a second time.

The Mullans moved to San Francisco and John, having spent some five years reading the law, passed the California bar exam.

Writes Petersen: “He would spend the next decade negotiating land deals that skirted both ethical and legal boundaries—a practice that brought him the prosperity he had long cherished, but at the cost of his carefully honed reputation.”

He and his partner Frederick A. Hyde mastered the state’s byzantine and largely unregulated land transfer system. They hired surrogates to buy public land that they then sold at considerably higher prices. As a Democratic Party activist, he fought Chinese suffrage, claiming America’s laws were to be administered “by white men, for the benefit of white men.”

In 1878, California Governor William Irwin appointed Mullan to collect money the federal government owed the state for federal land transfers. Mullan was to get a commission of 20 percent. He returned to Washington, D.C. Hyde expanded his land dealings to Oregon and Washington, where he was later convicted of fraud.

Mullan outfitted a Connecticut Avenue home with European furnishings and servants. He was rich but overextended. Soon states started to renege on promises of payment. With hundreds of thousands of dollars at stake, Republican opponents and the press piled on Mullan as a money grubber; California’s Republican Governor Robert Waterman dismissed him. Mullan wrote a 580-page book to make his case and started legal proceedings that went to the state Supreme Court, which ruled against him.

Oregon and Nevada also withheld payments. With Mullan’s health in decline, his daughter Emma campaigned for payment, securing a fraction of what he was owed.

By 1905, Emma and May, young society women and, as one newspaper put it, “belles of many dances given in the most elegant ballrooms in the city,” had to open a laundry to make ends meet. When he died on December 28, 1909, John Mullan was broke.

The newspapers of the day barely noted his passing. His road, meanwhile, saw solid use on various parts, particularly by miners and their suppliers. It helped Walla Walla dominate Pacific Northwest trade. Still, writes Petersen, it “proved a bust as an east-west, cross-mountain wagon highway.”

Infantrymen improved the road in 1879, leading to a spurt of use. But travelers were soon using the Northern Pacific Railroad, which went north of Lake Pend Oreille, a route Mullan preferred in retrospect.

Then, two years after Mullan’s death, the first automobile crossed Fourth of July Pass. The Yellowstone Trail Association, working to build a 3,700-mile route from Plymouth Rock to Puget Sound, put Mullan’s road on its route. This became U.S. Route 10, one of the nation’s original long-haul highways. It went on to become Interstate 90.

“You can bet those engineers were out there trying to figure out where’s the best way through the mountains,” says Petersen. “It was Mullan’s route.”

While many people wrote the route off as a failure, says Petersen, “he was ahead of his time. The technology to keep a route through those mountains clear wasn’t available to people in the 1860s. Otherwise it would have been a success then.”

Today, the highway’s 75-mile stretch across Idaho, which Petersen calls “the most scenic and the most difficult passage,” bears the name “Captain John Mullan Highway.”

Web extras

Story: Mullan Road Monuments

Story: Mullan Road Monuments

by Keith Petersen ’73

Gallery: Gustav Sohon and the Mullan Road

Gallery: Gustav Sohon and the Mullan Road

Gustav Sohon (1825–1903) was an artist, interpreter, and topographical assistant. Sohon executed some of the earliest landscape paintings of the Pacific Northwest.

On the web

1863 Fort Walla Walla to Fort Benton military map detail (PDF) Courtesy WSU Libraries Digital Collections

1865 Mullan miners’ map (PDF) Courtesy WSU Libraries Digital Collections