Whether he’s studying how wounds heal or he’s tagging a runner out at home plate, John E. Olerud ’65 knows two techniques to succeed: work hard and stick with it.

Olerud credits those lessons to the man who recruited him to Washington State University’s baseball team, Chuck “Bobo” Brayton. “He was one of those guys who taught you a lot of lessons about life, not just baseball,” he says.

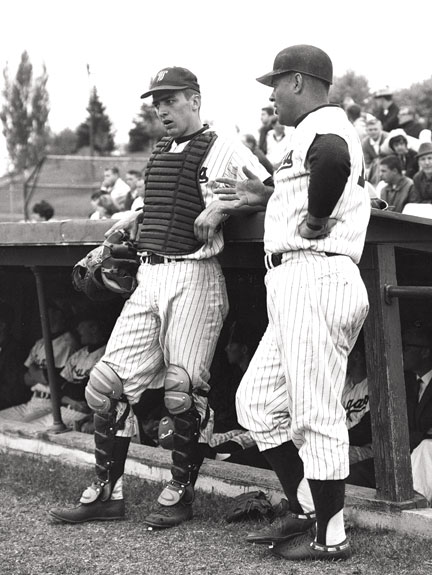

The lessons learned have led to achievements on the diamond—as catcher and captain of the 1965 Cougar baseball team that played in the College World Series, and as a professional player for seven years—and in academia, as head of dermatology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Olerud has many accolades. He was named to the WSU Athletic Hall of Fame in 1986, received numerous medical honors, and has published 92 refereed science and medical articles since 1974. Last December, he also received the Regents’ Distinguished Alumnus Award, the University’s highest honor given to alumni.

With two passions, and two careers, Olerud found that he can apply the same approaches to sports and science. As he researches the complex skin biology of healing wounds, Olerud the dermatologist recalls Bobo’s words to his players. “He used to have a saying—he probably wasn’t thinking it would apply to me as much later in life—‘A swinging bat is a dangerous bat. So when you’re up there, swing!’

“I haven’t always been the guy who gets the grant the first time, or gets the paper published in the good journal the first time. But I keep at it until I get it,” says Olerud.

Following his own mantra “Don’t let anybody outwork you,” Olerud was selected as a baseball All-American in 1965. “Don’t let anybody be better prepared than you are,” he says. “That’s very important on the baseball field, having all the bunt plays, the pick-off plays, the relays where you can have the little things that matter help.”

As a student, even with his success at baseball, he longed to pursue a childhood dream of becoming a doctor. “When I was a boy in Lisbon, North Dakota, there was a family doctor whose kids were about the same age as me,” he says. “I was always fascinated by being around his office and looking through his microscope.”

Olerud followed that path with encouragement from his academic mentor Herb Eastlick. “He took some ownership in getting me pointed in the right direction in terms of medical school,” he says. And he taught him some of the same lessons as Bobo. “He would tell you if there was something that you could be doing better,” he says.

When Olerud graduated with a bachelor’s degree in zoology in 1965, he wasn’t ready to choose one course over the other. So he pursued his medical degree at the University of Washington, at the same time playing professional baseball in the minor leagues with teams like the Seattle Angels, the San Jose Bees, and the Tulsa Oilers. The UW program made special arrangements to accommodate his sports career. “I could take two quarters of medical school and then play baseball for six months,” he explains.

When medical school was done, Olerud decided to retire from baseball and concentrate on research and medicine. He worked for the U.S. Navy for three years at a research lab at Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. His focus on sports medicine at UW led him to study rhabdomyolysis, a skeletal muscle tissue breakdown that recruits would get when they overexerted in training. He published several papers on his work there.

Olerud returned to Seattle, completed residencies at Harborview Medical Center, UW, and University Hospital, and then joined the faculty of the University of Washington. “I always wanted to be a teacher, but I could be a teacher in medicine,” he says, of blending two of his great interests. “So I’ve been an academic medicine person through my whole career.”

Olerud became fascinated with skin and its potential for basic science research. “It’s easy to get at the skin, the skin cells do all the same tricks that cells in other parts of the body do, and it’s an immune organ,” he says.

One major focus is on people with diabetes, whose wounds heal very slowly. “Patients with diabetes lose the nerves in their tissues, so could it be related to the neuropathy? Could it be related to the bacteria that live in the diabetic ulcers?” he asks. “Recently we’ve been doing research on bacterial biofilm and how the bacteria talk to the skin cells, and how the skin cells try to fight the bacteria.”

Olerud and his team are looking at that relationship and at strategies to get the new skin cells to migrate faster onto wounds. He is also working with other medical scientists and bioengineers to look at devices put through the skin, such as catheters, as well as connections between tissue and prosthetics. “The problem is always the interface between the skin and the device that goes through the skin,” he explains. Skin cells don’t tend to seal around an inserted device such as a titanium rod. Instead the skin hits the device and goes down into the body, followed by bacteria that can create dangerous infections around the implant.

The trick, says Olerud, was to figure out how to get the skin cells to attach. Part of the answer: holes in the device. “If you create little holes or little pores in the material, the skin cells migrate in and set up housekeeping inside the material,” he says. Olerud’s eyes light up as he describes the research.

Naturally, baseball continues to be part of Olerud’s life. Many associate the name “John Olerud” with his son and namesake, the stand-out Major League Baseball player and Cougar baseball star John Olerud x’88. The senior Olerud recognized young John’s ability and passion early. “I’d go to spring training and he was a little kid who really loved balls and to hit,” he says. “I remember once in spring training I was with the Montreal Expos organization, and we were in West Palm Beach, he’d be down there with this little plastic bat. I’d be throwing balls and he’d be ripping the balls into the surf. People would stop and say, ‘Wow, that little kid is good!’”

Though he ended his pro career, Olerud has never stopped working at the game. He and his Classics AAAA team, the Washington Titans, successfully defended their title in the top-level 60+ Legends World Series last fall in Florida.