Black History Month is both a celebration and a shame for Hasaan Kirkland (’99 MFA), an art professor at Seattle University and Seattle Central College.

It is a celebration in the sense that there is a lot to honor about African American history, African history, and the myriad complex contextual relationships that bind the two together.

Kirkland, who previously served as chief curator of the Northwest African American Museum in Seattle and before that as a studio fine art professor at Johnson C. Smith, a Historically Black College and University, knows this better than most.

(Courtesy WSU News)

He readily admits he could talk for days about the historical contributions of local Black artists and scholars as well as the lives of prominent national icons such as Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, Lois Mailou Jones, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, and David Driskell to name a few.

“Black History Month is a celebration because it gives us this time and the due elevation to show some relevant love, gratitude, perspective, acceptance, and profound respect to the contributions of Black people historically and today,” Kirkland says. “But at the same time, I think it is a weak offering and a dismissive compliment to note the contributions of Blacks in America and in the world in a month of time.”

After all, Black people were making significant political, cultural, agricultural, civic, scientific, and evolutionary contributions to the world before America was colonized and well before 1976 when February was administered as a month to be honored.

“Black History Month is not enough,” Kirkland says. “It is with perspective, grace, and mercy that it is received, but it is with honor, respect, and accountable gratitude that it should exist and be celebrated.”

Kirkland’s artwork often straddles the line between art and history, weaving the two together to bring exposure to the systemic racism and political, educational, economic, medical, and societal neglect Blacks have faced and continue to face today.

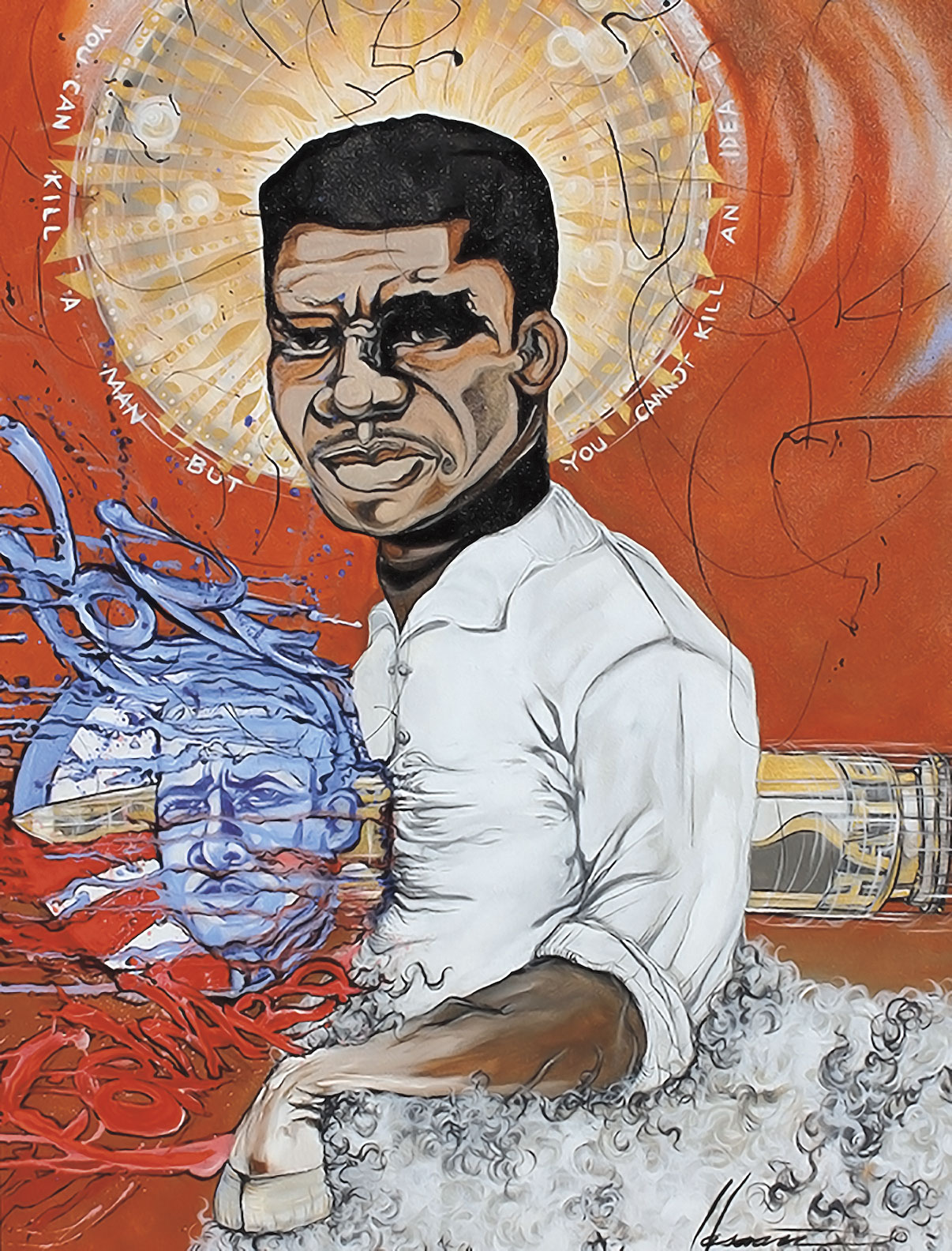

In his painting For Evers Hope, he attempts to capture the life, death, and legacy of Medgar Evers, a civil rights activist and World War II veteran who was shot dead in his driveway in Mississippi in 1963 for his work advocating for overturning segregation and increasing voting rights for African Americans.

Kirkland says the concept behind the painting was that while Evers was murdered for challenging the greater establishment, his beliefs and his sacrifice led to a future where the idea of a Black president and greater equality is even possible.

“It’s powerful because despite the oppression against Black men, women, and children, it conveys the secret to having boundless power over oppression,” Kirkland says. “You can reduce us or even kill us, but you cannot kill our ideas.”

For Evers Hope is among five of Kirkland’s recent paintings that helped earn him a Black Lives Matter Artist Grant from the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at Washington State University.

The grants recognized 20 artists from across Washington for their creative works responding to the Black Lives Matter movement, marginalized communities, and experiences with systemic racism and inequality. The works will be featured at the museum beginning in fall 2021.

“In my time in the state of Washington, I often noted the marginalization of Black artists and members of the Black community in the landscape of art or culture, as well as the lack and limited representation regarding positive imagery, thought leadership, inclusion, placement, and equitable artistic cultural expression and agency,” Kirkland says. “I would like to contribute to change that.”

One of the hardest things he says he’s struggled with throughout his award-winning career was the desire to be an artist on the same conceptual and literal platform as other artists and not just a “Black artist.”

A child of a military family who grew up traveling between diverse locations such as Turkey, England, France, and Japan, it wasn’t until coming back to the states to start high school in Tacoma and later attend WSU as a fine arts student that he discovered what this meant.

“Getting introduced to racism and the deep-seated prejudices that are generated from the existence of systemic oppression against people who look like me began to shape my desire to stand up, speak out, and develop my art and creative voice within the lens of social justice,” Kirkland says.

“The unfortunate regard I faced and continue to face forces me to manage twice the load: one to manage perception, complicit negligence, and the inescapable covert and overt judgement or critique by White counterparts brought on by my presence and involvement in the fine arts. The other: succeeding in the fine arts.”

Despite the challenges, Kirkland has gone from a young man inspired by comic books and graffiti to an internationally acclaimed painter and visual artist, who has published and exhibited in prestigious venues around the world throughout his 30-year career.

In addition to his role as a studio artist and educator in the Seattle area, he founded a visual art company, Kairos Industry, in 2010 and started a visual and performing arts honor society, Psi Rho Alpha, in 2014.

Kirkland is also pursuing a doctorate from the University of Washington where he is studying education—curriculum and instruction, and art as pedagogy and social justice.

“I am continuing my education as a means to expand my own career and creative intellect and deepen my discovery of reshaping the landscape of instruction and learning,” Kirkland says.

For Evers Hope, 2013, acrylic on canvas by Hasaan Kirkland (Courtesy WSU News)